Acclimatized Landscape

Solo exhibition. Cerrado Gallery.Goiânia, Brazil.

2024.

ACCLIMATIZED LANDSCAPE

Curator

"Paisagem aclimatada [Acclimatized Landscape], Talles Lopes’ first solo exhibition in Goiânia, brings together works that show the current development of the artist’s research. His investigations about space consider the forms of spatial representation as instruments of domination. In this way, he questions space as territory and treats it as a human construction based on political, economic, social and cultural issues, whose influence directs the way in which the concepts of cartography, landscape, landscaping, garden, farming and architecture are articulated.

Born in 1997 in Guarujá (SP) and living in Anápolis (GO), the artist - one of the most interesting and curious of his generation - has a degree in architecture. This discipline plays a prominent role in his production, which is dedicated to reflecting on the traces left on Brazilian space by the models of colonization and modernization implemented in the country. With a broad time span, his work reflects on Brazil, referring to sources from the history of art and architecture, statistics, botany and landscaping.

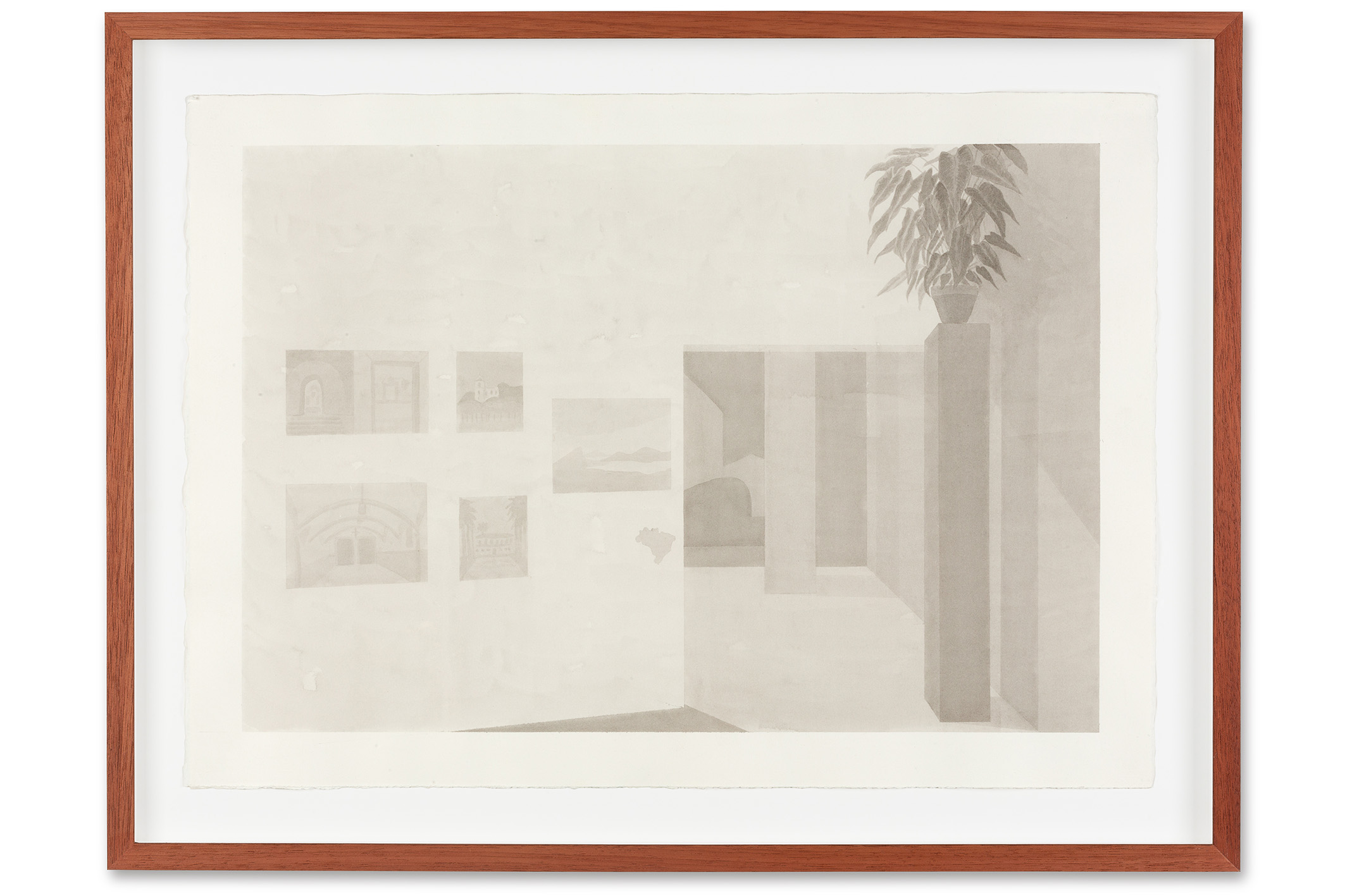

In Paisagem aclimatada [Acclimatized Landscape], Talles Lopes works with installation procedures, articulating relationships between paintings on canvas and drawings on paper arranged over abstract shapes painted on the walls. In addition, there are vases created in the 1950s by Swiss designer and architect Willy Guhl (1915-2004), containing ornamental plants. Arranged in the exhibition space, the vases create a landscape-garden acclimatized to the interior of Cerrado Gallery.

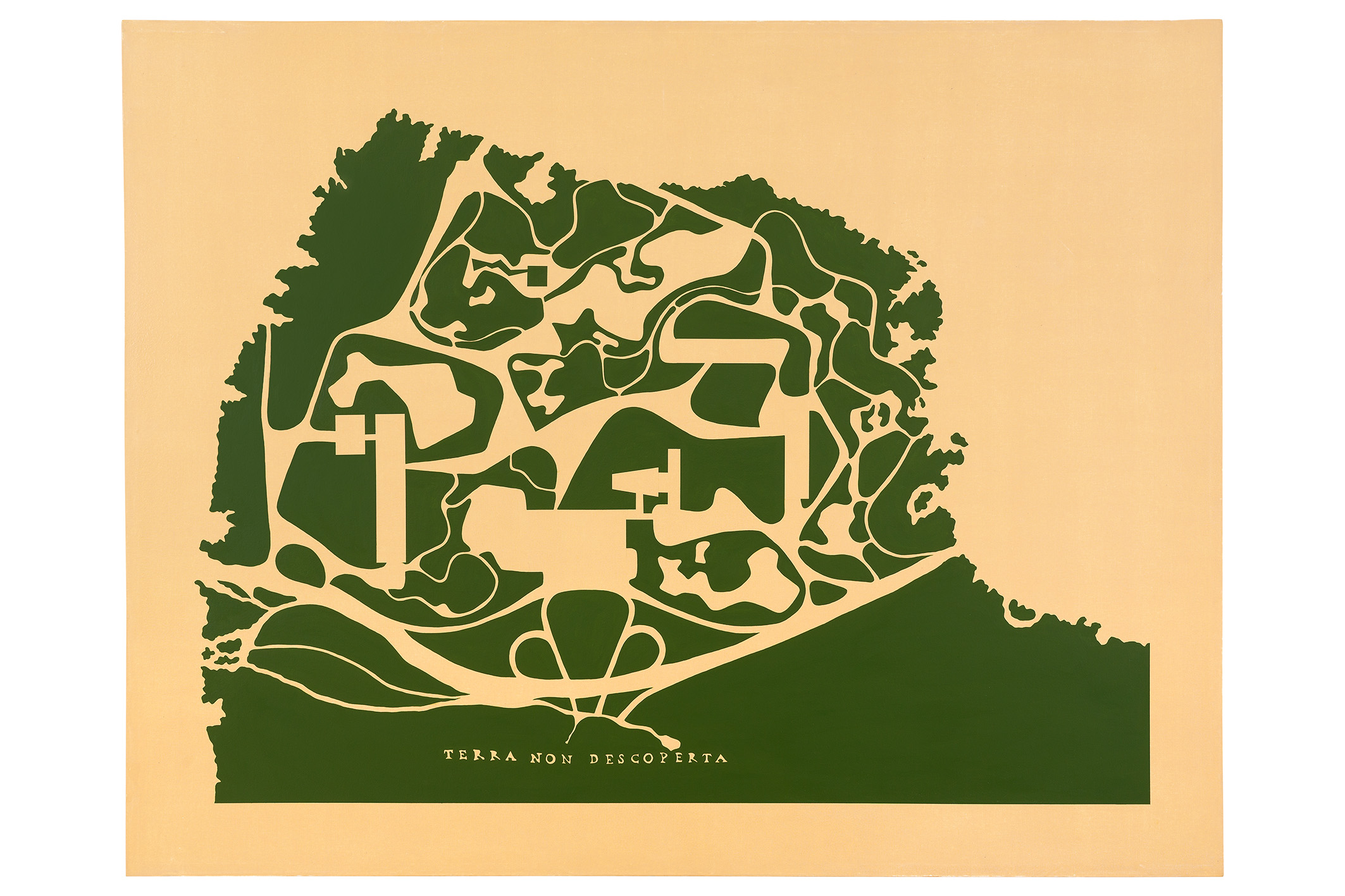

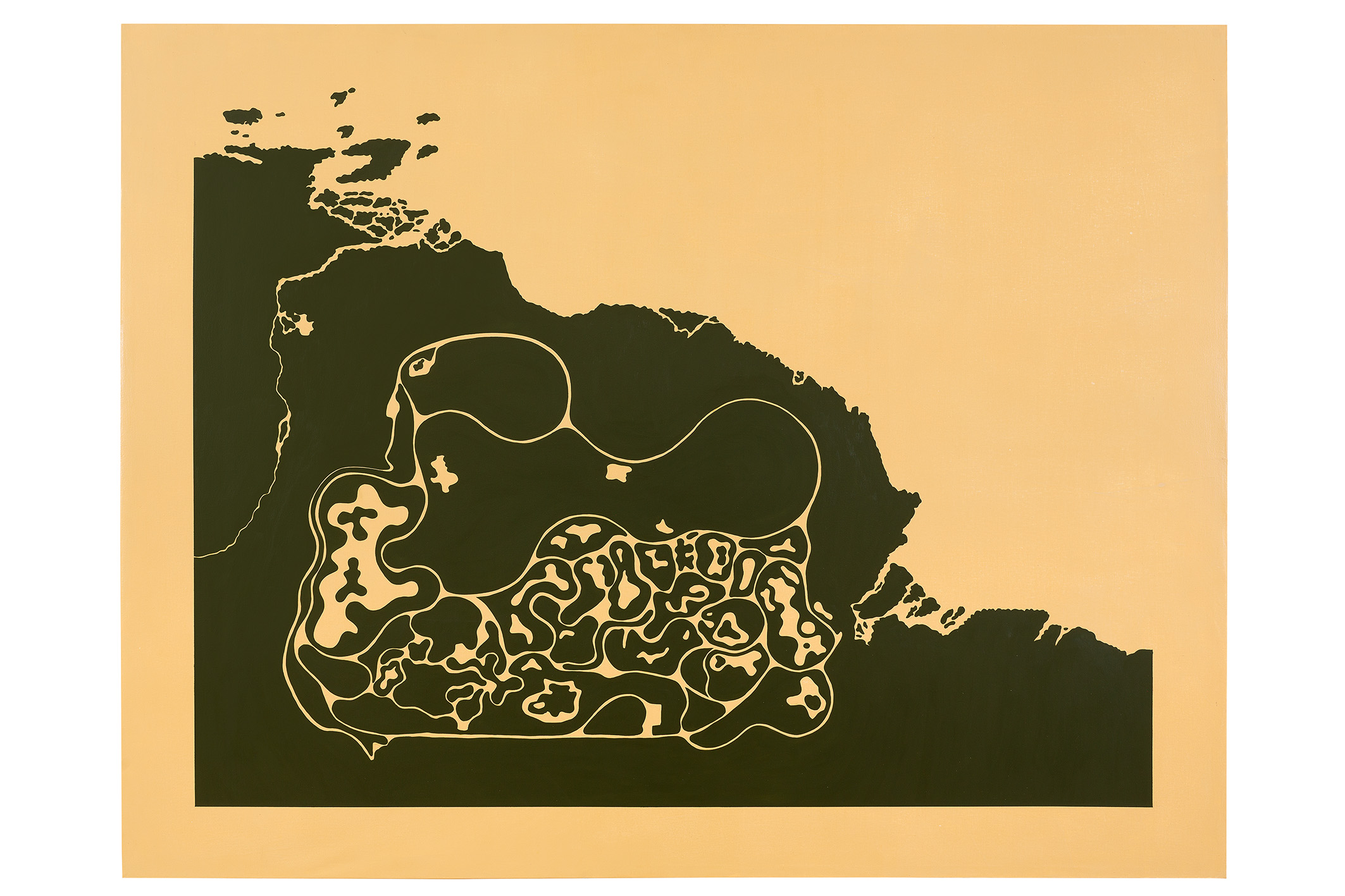

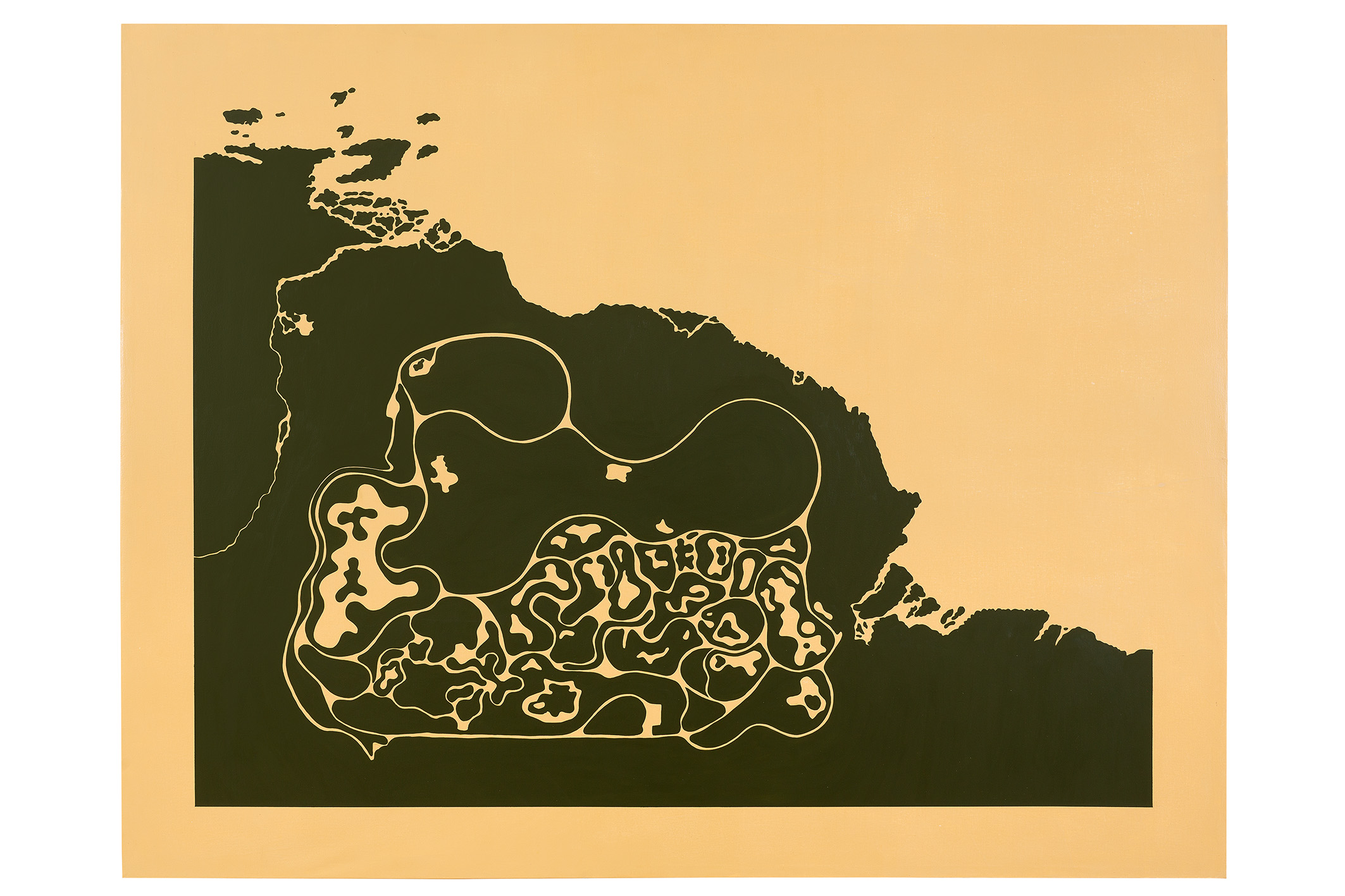

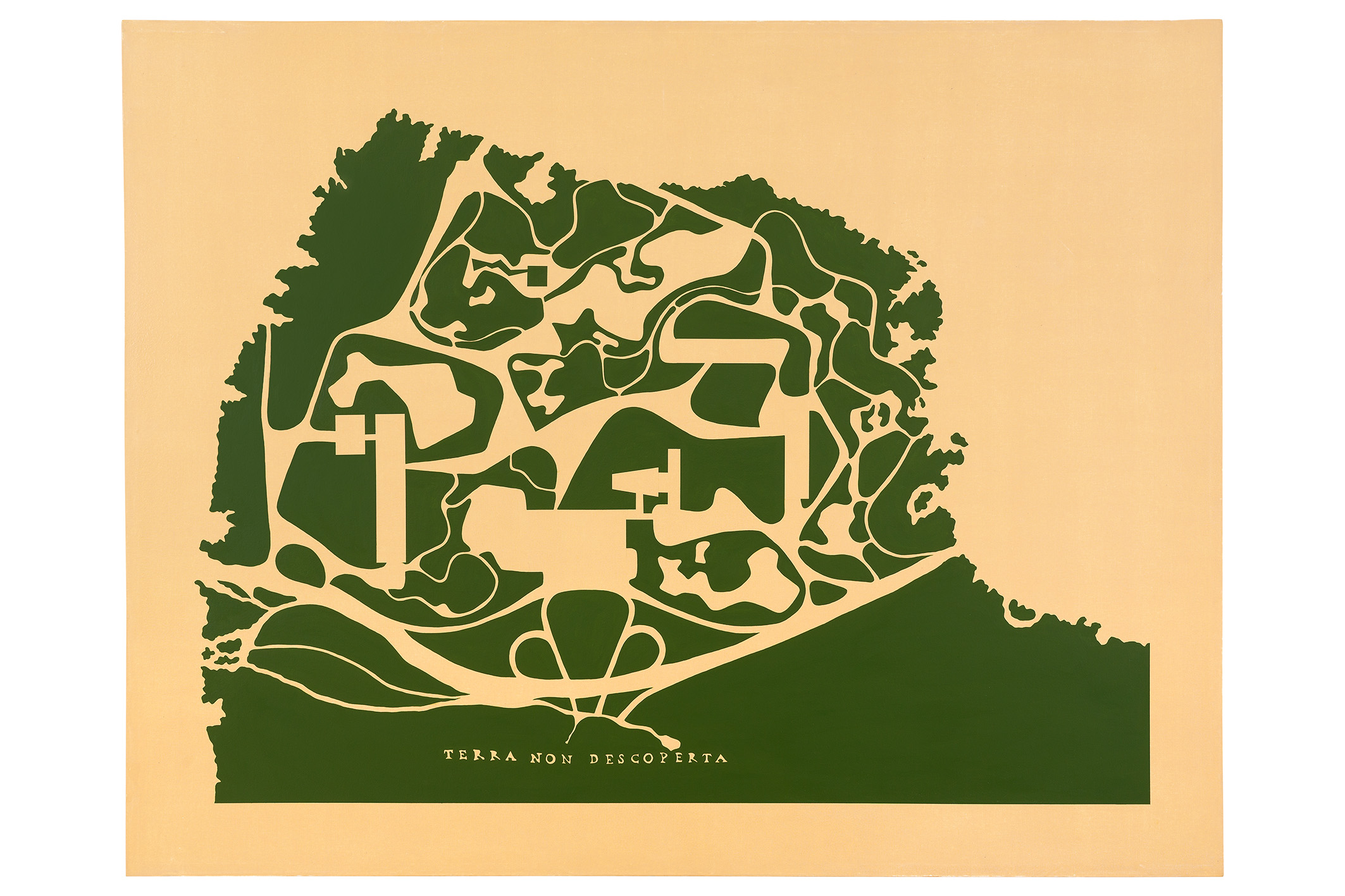

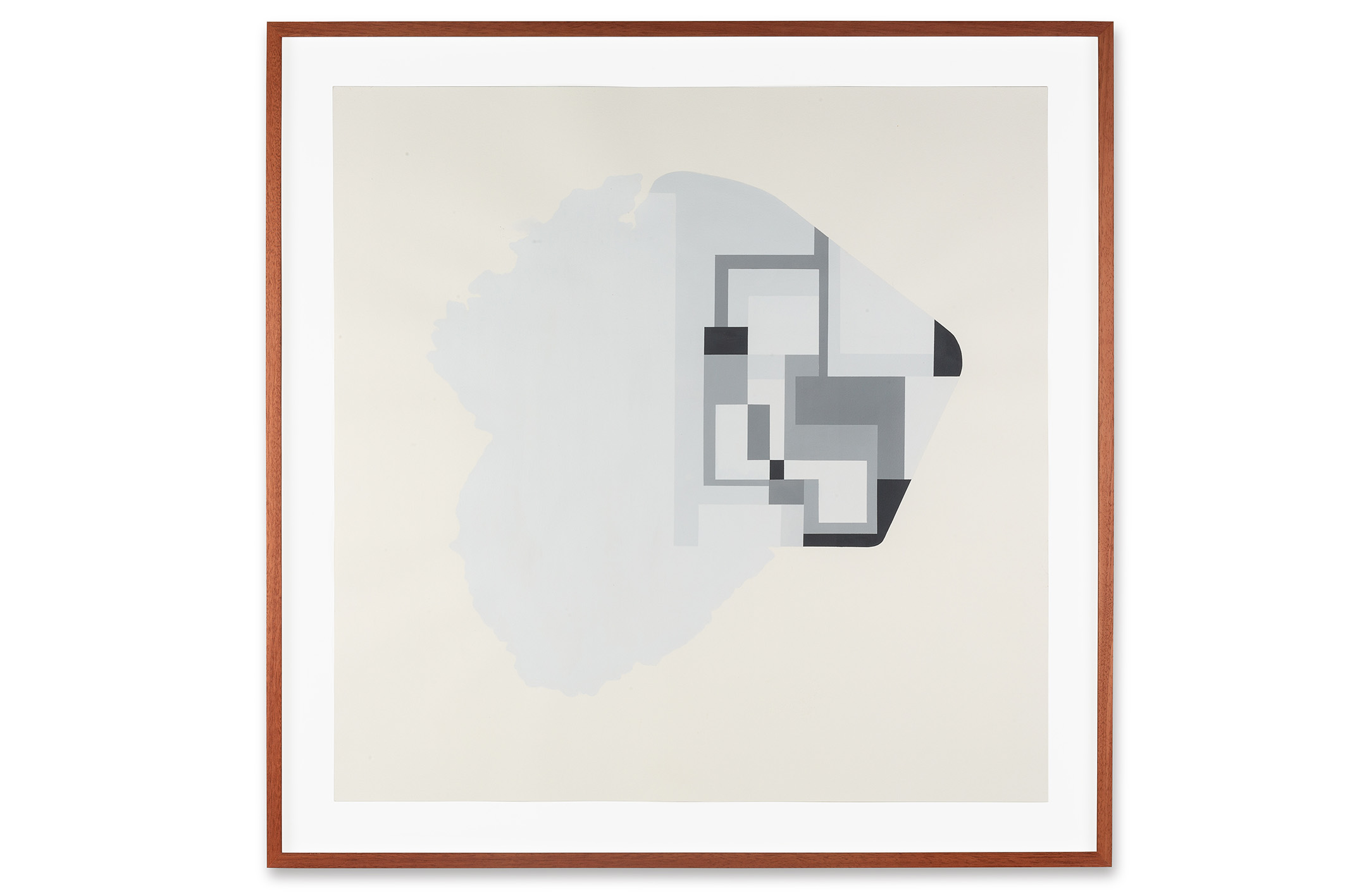

In his paintings on canvas, Talles Lopes applies the contours taken from cartographies of Brazilian territory made in the 16th and 17th centuries to landscaping projects by Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994), dating from the 1940s-50s. Burle Marx was responsible for the creation of modernist landscaping and the inclusion of Brazilian plants in projects, abandoning the need to import exotic species. Another painting superimposes the drawing of Dom-Ino House (1914), designed by Le Corbusier (1887-1965), on the map of Pernambuco. By doing so, it embeds the grinding gears of a colonial sugar cane mill in the architectural structure of the “free plan”. The painting reactivates the idea of a “living machine” contaminated by the idea of a machine for grinding enslaved people. A Swiss architect and urban planner, Le Corbusier had a major influence on Brazilian architecture as a consultant on the construction project for the Ministry of Education and Health building (1937-1943), an icon of modern architecture in Brazil.

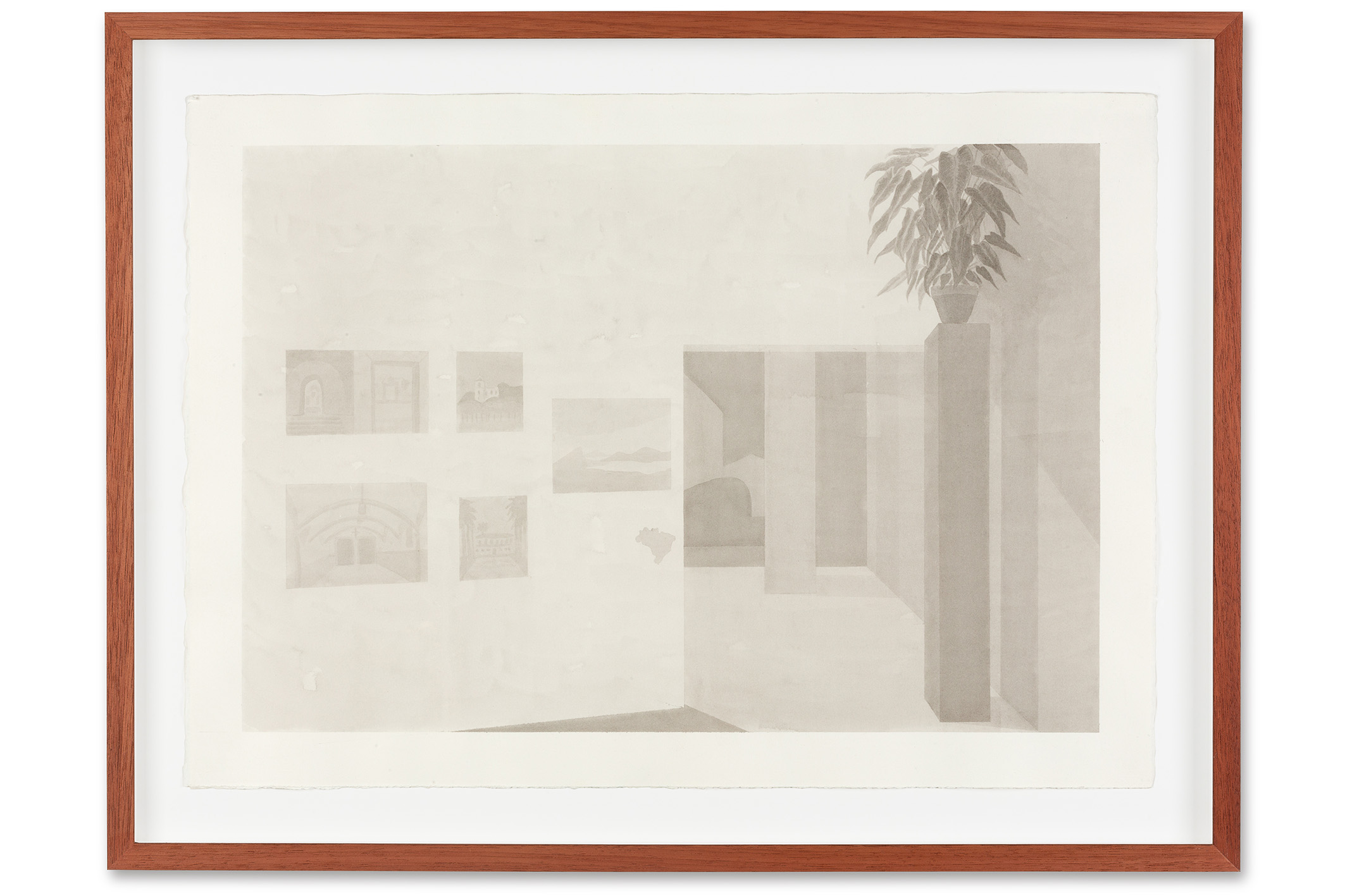

From this building, Talles Lopes cut out the shape of a decorative panel made in tiles by Candido Portinari (1903-1962) and painted it on the gallery wall. The shapes painted in positive or negative on the walls are not mere scenography for the exhibition. On the contrary, they bring references of great value and expand the scope of the artist’s research, such as the citation to the displays used at the Estado Novo National Exhibition, held between 1938 and 1939, as a balance of the country’s modernization and as propaganda for Getúlio Vargas (1882-1954). As a site specific, in the wall painting inspi red by the Ministry of Education and Health’s display at that exhibition, Talles Lopes inserts an original painting by Burle Marx. The set is accompanied by drawings reproducing some of his projects and the catalog of the important exhibition Brazil builds, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1943. The show displayed records of Brazilian architecture accompanied by specimens of ornamental plants from the national flora. On other walls are monochrome paintings executed on supports with abstract and organic shapes, inspired by the flowerbeds designed by Burle Marx for the garden of the former Ministry, now the Gustavo Capanema Palace."

Acclimatized landscape, in a way, discusses the changes brought about by the country's successive economic cycles, based on the exploitation of land and exotic plant species (sugar cane, cotton, coffee, soybeans) that transformed landscapes from the coastal strip to the interior, reaching the occupation of the vast North and Midwest regions with the advance of agribusiness. Colonizing the land and modernizing the territory in Brazil implies creating another landscape, different from the natural one, which was and is permanently acclimatized to generate the enrichment of a few exploiters.

FORM FREE BORDER / FORMA LIVRE FRONTEIRA

Architect

“And since the movements of the spirit precede the manifestations of the other forms in society, it is easy to see the same tendency towards freedom and the conquest of expression both in the imposition of free verse before 1930 and in the ‘march to the West’ after 1930”.[i]

Mario de Andrade, The Modernist Movement, 1942.

In this key passage from his famous critical review The Modernist Movement published in 1942, Mario de Andrade associates the free form established by the modernist revolution with the colonization project for Central Brazil led by the dictatorial regime of the Estado Novo, the so-called March to the West. “The true meaning of Brazilianness”, stated Getúlio Vargas, appropriating the modernist esthetical vocabulary, “is the March to the West”. Gilberto Freyre attributed the same modern-national meaning to what he called self-colonization: “the colonization of Brazil soon ceased to be strictly European and became a process of self-colonization: a process that would take on a national character after independence”. In Vargas’ words, it was “our imperialism”, that is, a national imperialism, aimed at conquering and colonizing its own territory.

Free form and the expansion of the colonial border meet in the “conquest of expression”, substances of the same project of modernity and national identity. More than that, what Mario de Andrade lets us understand is that the movement of the borders (as well as industrialization, its urban parallel), is the very social expression of freedom and modernity announced by the aesthetics of modernist free form.

The understanding that national identity and the modernization of the country are associated with the conquest and colonization of the territory found in the modern movement one of its main ideological avatars, especially through architecture.

Brasília, a border city par excellence, “is a deliberate act of possession”, wrote urban planner Lucio Costa in the memorial to the Pilot Plan, “a gesture with a sense of still being a pioneer, along the lines of the colonial tradition.” For curator and art critic Mario Pedrosa, Brasília’s modern project was to be found in the symbolic and political force of this (neo)colonizing gesture: “the full recognition that the possible solution was still based on the colonial experience, in other words, a Cabraline-style taking of possession”.

The link between coloniality and modernity, whose ideological origin lies in the racialized and racist thinking that identified the architecture of Portuguese colonialism as the founder of the national artistic tradition, shaped the “tropical” and “baroque” language of what would come to be internationally revered as “the Brazilian style” in modern architecture. With its free, curvilinear, sinuous and abstract forms, with all its exuberance and tropical sexualization, Brazilian modern architecture concealed the political and ideological foundations of its colonial heritage, or rather made them its patrimony, communicating images of the colonial-modern border as a movement towards progress, racial democracy, and the formation of national identity.

[i] Mario de Andrade, O Movimento Modernista, Rio de Janeiro: Casa do Estudante do Brasil, 1942, p. 63-65. The passage in full is: “And since the movements of the spirit precede the manifestations of the other forms of society, it is easy to see the same tendency towards freedom and the conquest of self-expression both in the imposition of free verse before 1930, and in the ‘march to the West’ after 1930; both in ‘Bagaceira’, ‘Estrangeiro’, ‘Negra Fulô’ before 1930, and in the case of Itabira and the nationalization of heavy industries, after 1930”.