MOMUMENAL SURPLUS

MAPA (Museum of Plastic Arts of Anápolis)

2021

SPACE, HISTORY, CARTOGRAPHY AND ARCHITECTURE IN THE WORK OF TALLES LOPES

Text by Divino Sobral

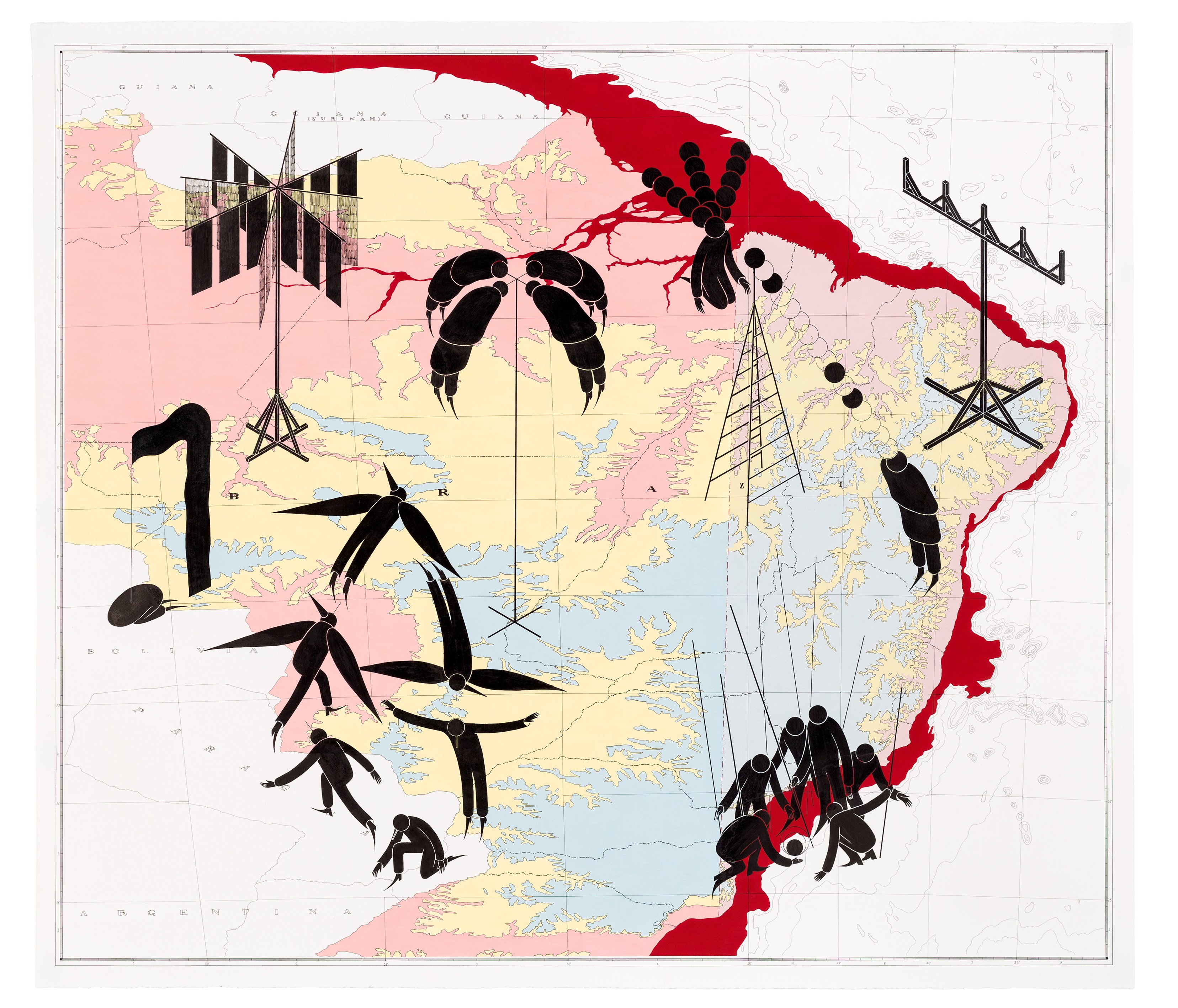

In his first solo exhibition, Talles Lopes deepens his research on space, having as major references the histories of cartography and architecture. He is an artist and researcher who delves into the layers of meanings disposed in mapping, recognition, construction, use, and representation of space, understood as a set of relationships between elements of physical and social order. His interest turns, especially, to the place where the human experience tales place, called Brazil.

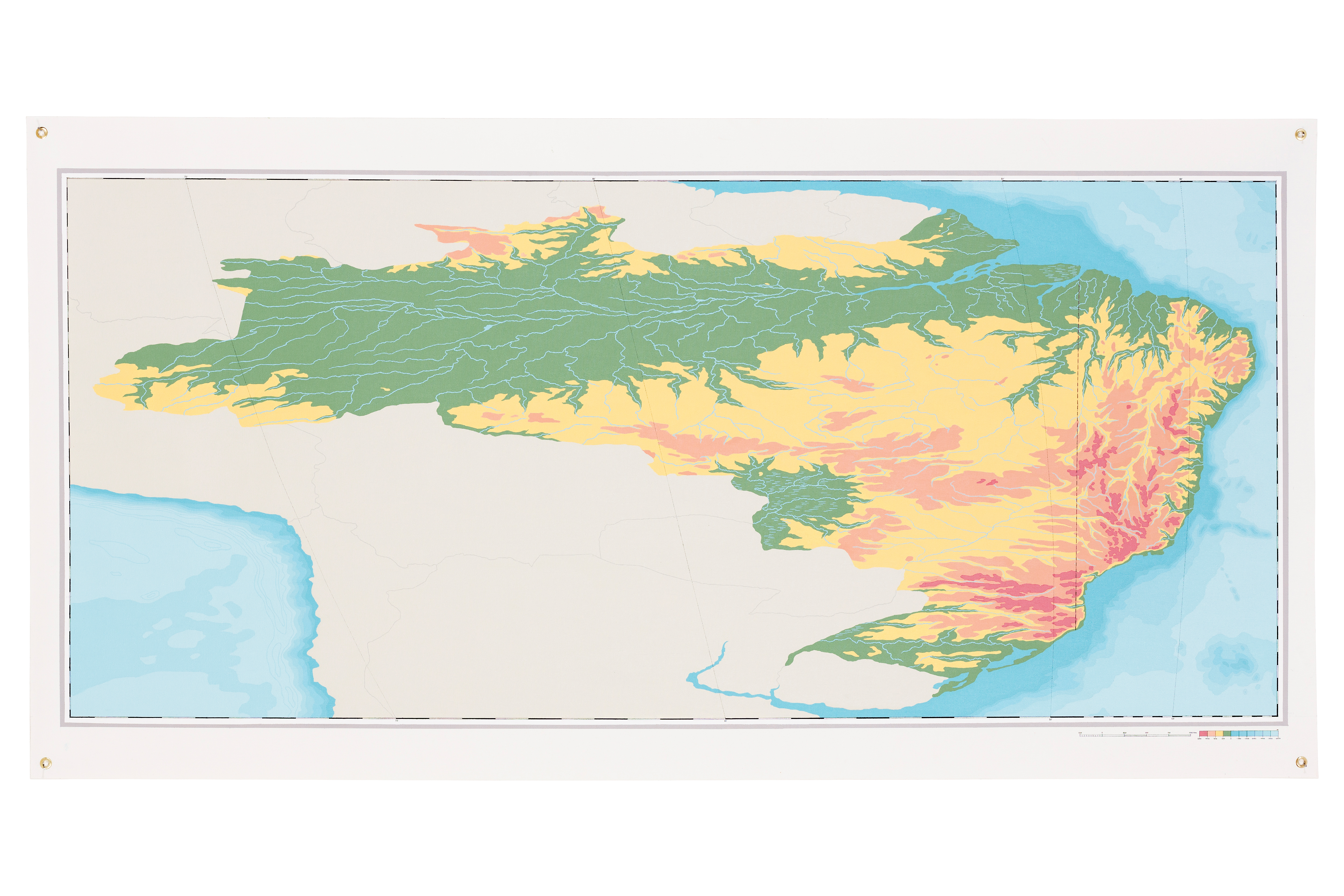

The artist problematizes the map as a visual record of space and a measurement of the actions that take place in it. He emphasizes the role of cartography both as art and as an ideological tool of control over territory, and, using cartographic conventions, comments on everything from the invention of cartographic space to actual statistical data concerning social, economic, and political issues.

Talles Lopes reflects on the representation of the country’s interior in cartography made from the 16th century to the 1960s, and observes in the colonial maps the complete distinction between the wild interior and the civilized coast where the Portuguese invasion and colonization started; notes that the abundant mineral riches in the unknown wilderness drove the ambition of the bandeirantes (explorers), who caused the expansion of the territory at the cost of genocide; points out that the modern project of national integration and occupation of demographic voids, promoted by Getúlio Vargas with the Marcha para o Oeste (March Westward), is similar to another modernizing program of Juscelino Kubitschek, which led to the creation of Brasília in the Central Plateau.

For the artist, the production of the maps that accompanied the discourses of occupation and modernization of the Brazilian interior was updated according to the interests of each era, and remained with the same argumentation of an undominated place to be permanently occupied and explored.

In ‘A Marcha’ (2018) and ‘Mapa estriado’ (2020) he employs the Tordesillas Meridian (1494) - created by the diplomatic treaty dividing the lands belonging to Portugal and Spain on the American continent - to create from it an anamorphosis, a type of cartographic deformation that emphasizes the endless and unreachable, the always unknown Brazilian interior, which expands in an aggravated way towards the west. The result of the deformation is a representation of the monumentality of the country’s interior, and also a metaphor for the current difficulty in overcoming the permanence of the colonialist-based arguments imposed over the territory for more than five centuries.

Without the theater of power and taken to the interior of the gallery, the columns grow before the body in the same intensity in which they show themselves as parody, making fun of the great modernist architecture, they exhibit a humor that arises in large part due to the aspects of the materials used, the mason’s bill, the plaster as surface finish, and also the piled up way of displaying the pieces assumedly carnivalized.

Between quotation and appropriation, Excedente monumental either results in a scenographic architecture that criticizes the theatricality of the original column, whose unique characteristics make the opulence, elegance, lightness, grace and power of the Alvorada Palace, or reflects the presence of popular and anonymous architecture that appropriated Niemeyer’s form and recreated it in different contexts, scales, techniques and materials in Brazil.

Talles Lopes’ training as an architect is clearly shown in works dedicated to inventorying aspects of national architecture, surveying popular production created under the influence of erudite modern work through the appropriation of the canonical, in a movement that starts from the center and reaches the peripheries. This is how the artist rewrites the history of architecture in Brazil in the work constituted as a book and entitled ‘Construção Brasileira: arquitetura moderna e antiga’ (2018).

The work rehearses the catalog of the exhibition ‘Brazil builds: Architecture new and old 1652-1942’, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MOMA) in 1943. The exhibition bore the signatures of the museum’s director, architect Philip Lippincott Goodwin (1885-1958), and photographer Kidder Smith (1913-1997), who also signed the catalog, which became a reference publication on national architecture.

Following the principles of the original layout, in ‘Construção Brasileira: arquitetura moderna e antiga’ Talles Lopes recreates the publication with another narrative, inserting photographs, taken from street view, of forty buildings built in fifteen Brazilian states, which appropriate the column of the Alvorada Palace as a symbol of the modernization that reached Brazil after the second half of the 20th century.

These are residential construction projects of unknown authorship and a markedly popular nature, which make exaggerated use of the column as ornament, employing materials and colors on the order of kitsch, and thus the realm of dubious taste and provincial flavor joins the desire to demonstrate modern vision and social distinction.

In the exhibition, the book ‘Construção Brasileira: arquitetura moderna e antiga’ is displayed for public handling on a wooden shelf, affixed to the wall at the height of a base. It is placed in close proximity with two other elements: on the wall: ‘Estudo para Excedente monumental’ (2020), a watercolor representing a column of the Alvorada; ‘in space: Untitled’ (2021), a ready-made that is partly an industrial object and partly a living being, in short, a pot in which a Swiss cheese plant (Monstera deliciosa) is planted.

Here there is the alignment of different operations of the artist to reflect on Brazilian architecture and the ways of presenting it. Situated as a ready-made, the vase appropriated by Talles Lopes is signed by Willy Guhl (1915-2004), Swiss architect and designer, member of the neo-functionalist movement that worked focused on the research of new materials during the reconstruction of Europe after the Second World War. The round model used by the artist is part of a series of vases with modernist lines created in the early 1950s for the Swiss company Eternit and produced with a mixture of concrete and asbestos. Guhl’s vases were also manufactured in Brazil and began to accompany the modernization of the domestic landscape of the middle classes.

Exuberant and very plastic, the Swiss cheese plant (Monstera deliciosa) was part of the list of ornamental plants that were exhibited among photographs, houseplants and models, in the exhibition ‘Brazil builds: Architecture new and old 1652-1942’. With this operation, Talles Lopes resumes MOMA’s expographic proposal of putting in dialogue modernist architecture and tropical landscape, while reaffirming Guhl’s intervention in Brazilian gardening. It is necessary to note that native plants only had their plastic potential for landscaping recognized and used in the second half of the 1930s. Previously the taste for exotic, mainly European, species predominated.

Landscape is one of the genres Talles Lopes uses to think about and approach the modernization of space resulting from technical development, economic progress, and the installation of the new as a strategy to overcome the old. He investigates landscapes in inland and distant places in Brazil, marked by isolation and backwardness, dominated by buildings that somehow reproduce the canonical form of modernist architecture, the column of the Alvorada Palace, symbol of modern Brazil turned towards progress and the future embedded in the popular imagination after the construction of Brasília.

Executed from a street view photograph that has peculiar distortions, made with a historical painting scale, the imposing painting ‘Clube Belavistense’ (2021) depicts a landscape of Bela Vista, a small town on the border of Mato Grosso do Sul with Paraguay, and focuses on the strange construction raised on the corner of two streets of pitted asphalt; exceptional for the context around it, the construction draws attention by the size of its built area and by the presence of an architectural design that cites the Alvorada column. On the distant border it displays to the neighboring country the sign of modernity intended for all the country’s borders.

‘The great waterfront of Novo Aripuanã’ (2020) is an installation composed of two elements: a painting representing the landscape of the port city of Novo Aripuanã, on the banks of the Madeira River, in Amazonas; a wooden replica of a bench in a square in the city of Três Lagoas, in Mato Grosso do Sul. Both address the appropriation of the Alvorada column by official constructions, linked to the municipal sphere. There is in the architecture of the port a mention of the patriotism typical of the period of the Military Dictatorship, expressed in the façade where one can read “We love Brazil”.

The small bench positioned in the space in front of the painting contemplates the harbor landscape. In this work, very distinct Brazils, the Amazon and South Mato Grosso interiors converse quite closely as they replicate the same icon of modernity. Through this installation, Talles Lopes thinks the unity and diversity of Brazil, and simultaneously calls up the different histories of its occupation, its construction, and its modernization.

Goiânia, October 2021