Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old

2018

"Talles Lopes is interested in domestic space, but from a historical perspective - what led residents of popular neighborhoods in different regions of Brazil to appropriate the columns that are part of the iconic architecture of the Planalto Palace in Brasilia? What are the boundaries between the official architecture of a country and its kitsch use? An artist-researcher, Talles makes a publication that cites the classic catalogue "Brazil Builds" (1943) and seeks (ironically) for this "Brazilian build".

Raphael Fonseca.

Curator, Denver Art Museum.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old

2018

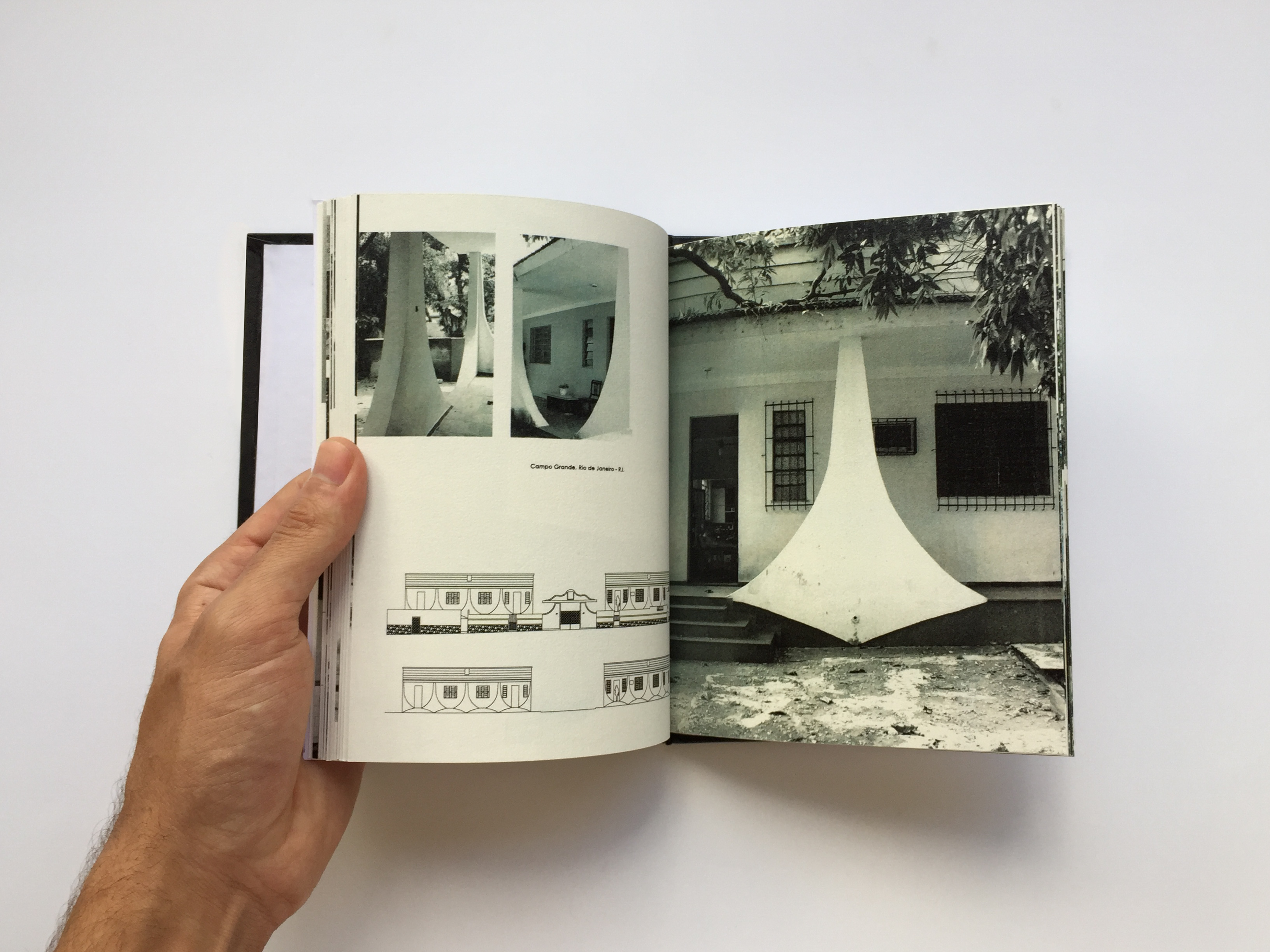

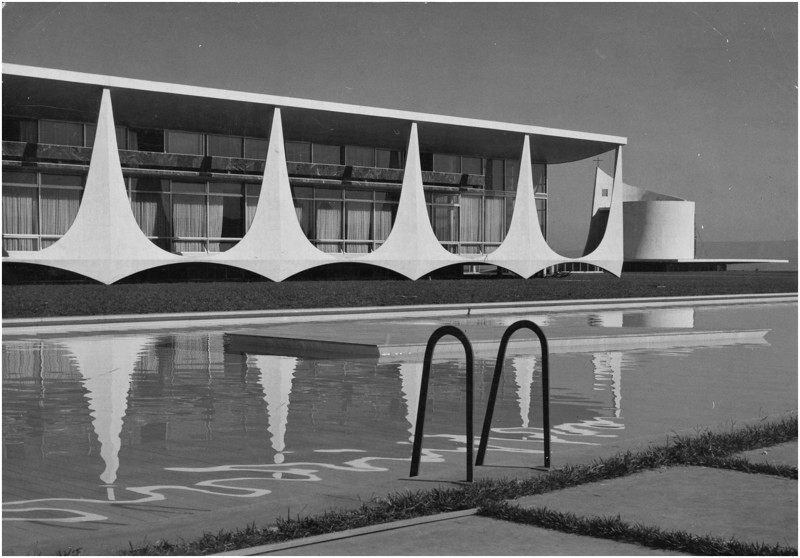

"Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old" is a research in development since 2017, based on the mapping and documentation throughout Brazil of popular constructions that appropriated architectural elements of Brasilia, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the official residence of the President of the Republic designed by modernist architect Oscar Niemeyer.

The research began in the interior of Goiás state, when the artist and architect Talles Lopes witnessed a variety of unofficial constructions that replicated the shape of the colonnade and other modernist elements. Because it appropriated Modernist stylistics without following the guidelines of the Modern Movement, this type of architecture has often been called "Kitsch"[1] or "Popular Modernism"[2] . They are constructions made by non-architects (bricklayers, designers, engineers and often by the residents themselves) possibly throughout the 1960s after the massive media coverage of the construction of Brasília.

![]()

![]()

Based on the verified absence of architects in the country's interiors until the mid-1970s [3], added to the foundation and vertiginous expansion of urban centers in Brazil after the construction of Brasilia, it can be deduced that most of the spaces built under the modernity ideology were produced by non-architects, subjects responsible for the edification of a significant part of the built landscape in Brazil.

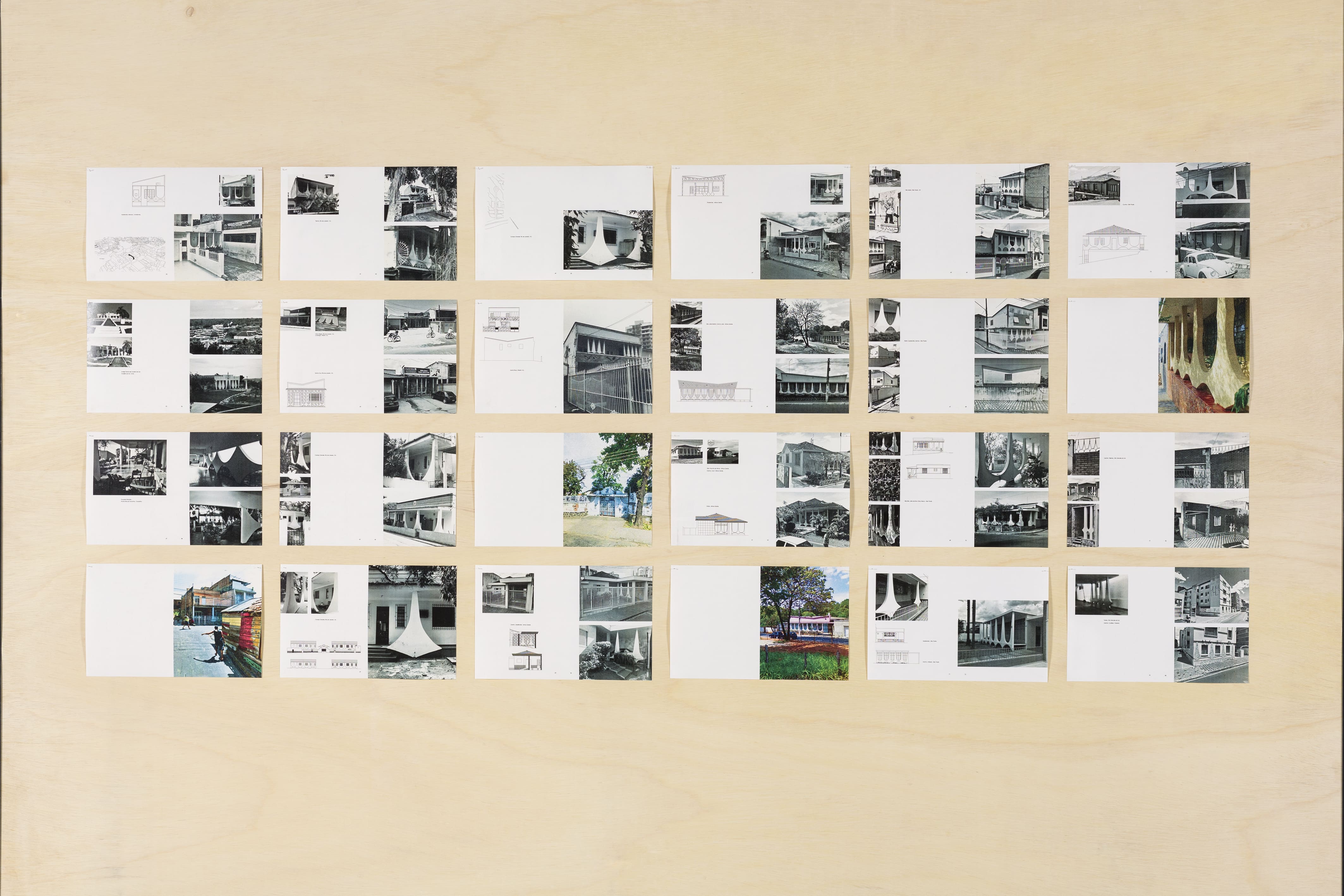

Concerned with the evident historiographic gap regarding these spaces produced on the periphery of modern thought, Brazil Builds has cataloged more than 100 of these constructions in 22 Brazilian states, in addition to 10 other examples documented in different countries around the globe (Guatemala, Egypt, USA, Iran, Portugal and Paraguay). Documentation was made possible through a method that associates keyword searches on social platforms, Wikipedia searches, and bibliography on popular architecture, added to long investigations through Google Street View.

The project proposes to bring this fascination with modernism in Brasília closer to one of its historical precedents: the exhibition and its homonymous catalog "Brazil Builds: Architecture new and old, 1652-1942", held at MoMA in 1943, organized by Philip Goodwin with images by photographer Kidder Smith. From a historical perspective, the exhibition presents a panorama of Brazilian modernist buildings, but like Brasilia, it strives to propose this architecture as supposedly representative of a national unity.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Brazil Builds narrates a modernity triumphant for its ability to adapt to the tropics, it fabricates an architecture that could modernize the third world to the extent that it was mixed in the cultural, geographical and climatic sphere, in a veiled and suspicious convergence with the current discourses of a racial democracy. In this sense, Brazil Builds anticipates Brasília and advocates for modernist architecture as the authentic representative of a supposed "Brazilian people", even if contradictorily this architecture was the exception in the landscape inhabited by these subjects.

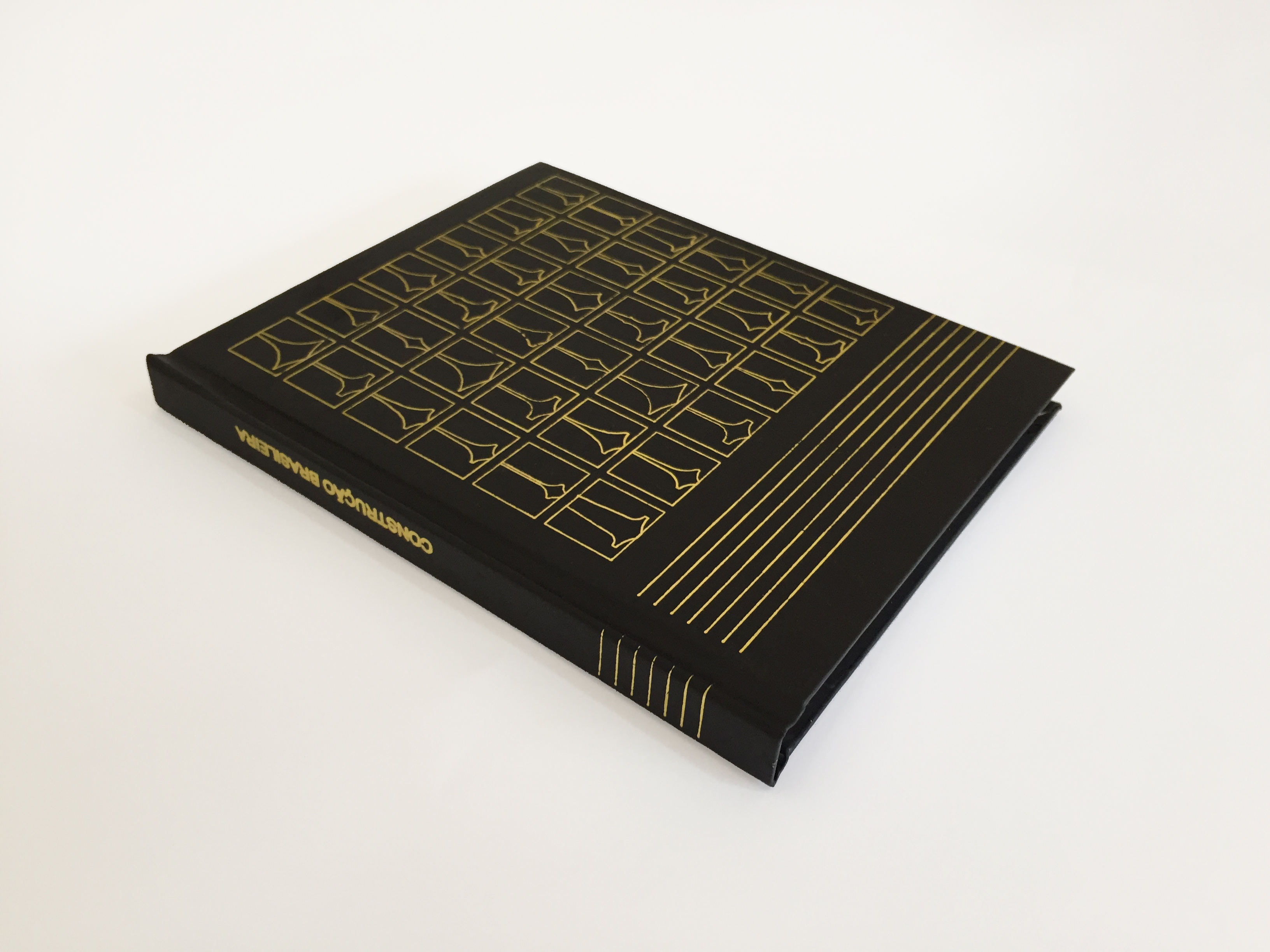

The popular classes, this abstract and heterogeneous category often ignored by modernization cycles, but called upon to compose the narrative of the modern movement, establishes a counterpoint by appropriating modernist architecture in the figure of the Alvorada Column, to elaborate their own senses of modernity. Thus, "Brazil Builds" proposes to understand this process through the fictionalization of an architecture catalog, appropriating the design and layout of the classic Brazil Builds catalog to present this collection of unofficial architecture scattered throughout Brazil.

Dissolving the boundary between official and unofficial narratives about modernity in Brazil, but like Caetano, speculating that it remains to be seen that there are many unfathomed levels, many mysterious stages in the relations between the masses and what is conventionally called modernity [4] .

[1] GUIMARÃES, Dinah; CAVALCANTI, Lauro. Arquitetura kitsch: suburbana e rural. Ed. II. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1982.

[2] LARA, Fernando Luiz Camargos. “Modernismo Popular: elogio ou imitação?”. Cadernos de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, v. 12, n. 13, Dec 2005, pp. 171-184.

[3] SEGAWA, Hugo. Arquitetos peregrinos, nômades e migrantes. In: Interlocuções na arquitetura moderna no Brasil: o caso de Goiânia e de outras modernidades. Goiânia: Universidade Federal de Goiás-UFG, 2015.

[4] VELOSO, Caetano. Texto para o catálogo Des maisons comme des tableaux (Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1988). In: Mariani, Anna. Pinturas e Platibandas. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2010.

Raphael Fonseca.

Curator, Denver Art Museum.

Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old

2018

"Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old" is a research in development since 2017, based on the mapping and documentation throughout Brazil of popular constructions that appropriated architectural elements of Brasilia, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the official residence of the President of the Republic designed by modernist architect Oscar Niemeyer.

The research began in the interior of Goiás state, when the artist and architect Talles Lopes witnessed a variety of unofficial constructions that replicated the shape of the colonnade and other modernist elements. Because it appropriated Modernist stylistics without following the guidelines of the Modern Movement, this type of architecture has often been called "Kitsch"[1] or "Popular Modernism"[2] . They are constructions made by non-architects (bricklayers, designers, engineers and often by the residents themselves) possibly throughout the 1960s after the massive media coverage of the construction of Brasília.

Based on the verified absence of architects in the country's interiors until the mid-1970s [3], added to the foundation and vertiginous expansion of urban centers in Brazil after the construction of Brasilia, it can be deduced that most of the spaces built under the modernity ideology were produced by non-architects, subjects responsible for the edification of a significant part of the built landscape in Brazil.

Concerned with the evident historiographic gap regarding these spaces produced on the periphery of modern thought, Brazil Builds has cataloged more than 100 of these constructions in 22 Brazilian states, in addition to 10 other examples documented in different countries around the globe (Guatemala, Egypt, USA, Iran, Portugal and Paraguay). Documentation was made possible through a method that associates keyword searches on social platforms, Wikipedia searches, and bibliography on popular architecture, added to long investigations through Google Street View.

The project proposes to bring this fascination with modernism in Brasília closer to one of its historical precedents: the exhibition and its homonymous catalog "Brazil Builds: Architecture new and old, 1652-1942", held at MoMA in 1943, organized by Philip Goodwin with images by photographer Kidder Smith. From a historical perspective, the exhibition presents a panorama of Brazilian modernist buildings, but like Brasilia, it strives to propose this architecture as supposedly representative of a national unity.

Brazil Builds narrates a modernity triumphant for its ability to adapt to the tropics, it fabricates an architecture that could modernize the third world to the extent that it was mixed in the cultural, geographical and climatic sphere, in a veiled and suspicious convergence with the current discourses of a racial democracy. In this sense, Brazil Builds anticipates Brasília and advocates for modernist architecture as the authentic representative of a supposed "Brazilian people", even if contradictorily this architecture was the exception in the landscape inhabited by these subjects.

The popular classes, this abstract and heterogeneous category often ignored by modernization cycles, but called upon to compose the narrative of the modern movement, establishes a counterpoint by appropriating modernist architecture in the figure of the Alvorada Column, to elaborate their own senses of modernity. Thus, "Brazil Builds" proposes to understand this process through the fictionalization of an architecture catalog, appropriating the design and layout of the classic Brazil Builds catalog to present this collection of unofficial architecture scattered throughout Brazil.

Dissolving the boundary between official and unofficial narratives about modernity in Brazil, but like Caetano, speculating that it remains to be seen that there are many unfathomed levels, many mysterious stages in the relations between the masses and what is conventionally called modernity [4] .

[1] GUIMARÃES, Dinah; CAVALCANTI, Lauro. Arquitetura kitsch: suburbana e rural. Ed. II. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1982.

[2] LARA, Fernando Luiz Camargos. “Modernismo Popular: elogio ou imitação?”. Cadernos de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, v. 12, n. 13, Dec 2005, pp. 171-184.

[3] SEGAWA, Hugo. Arquitetos peregrinos, nômades e migrantes. In: Interlocuções na arquitetura moderna no Brasil: o caso de Goiânia e de outras modernidades. Goiânia: Universidade Federal de Goiás-UFG, 2015.

[4] VELOSO, Caetano. Texto para o catálogo Des maisons comme des tableaux (Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1988). In: Mariani, Anna. Pinturas e Platibandas. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2010.