BIO

Talles Lopes is an artist and architect who graduated from the State University of Goiás. He lives and works in Anápolis, a city in the interior of central Brazil, where he is a co-founder of Barranco Ateliê, an independent art space. Reviewing archives, atlases, architectural projects and exhibition catalogs, the artist has dedicated himself to investigating the landscape built on the periphery of modern thought in Brazil, as well as the suspicious relationship between the imaginary of modernity and colonial heritage.

The artist has taken part in exhibitions such as the 12th São Paulo International Architecture Biennial (2019), the "Brazilian Stories" exhibition (2022) at MASP - Museu de Arte de São Paulo, as well as the "Concretos" exhibition (2022) at TEA - Tenerife Espacio de las Artes (Spain), and was also awarded the EDP Prize in the Arts (2020), held at the Tomie Ohtake Institute. He has been a resident artist at the Delfina Foundation in London (2022), the URRA Project in Buenos Aires (2023), at the IPA - Institute for Public Architecture (2023) and The Watermill Center (2024), both in New York.

The artist has taken part in exhibitions such as the 12th São Paulo International Architecture Biennial (2019), the "Brazilian Stories" exhibition (2022) at MASP - Museu de Arte de São Paulo, as well as the "Concretos" exhibition (2022) at TEA - Tenerife Espacio de las Artes (Spain), and was also awarded the EDP Prize in the Arts (2020), held at the Tomie Ohtake Institute. He has been a resident artist at the Delfina Foundation in London (2022), the URRA Project in Buenos Aires (2023), at the IPA - Institute for Public Architecture (2023) and The Watermill Center (2024), both in New York.

CV

︎RESIDENCIES

2024

2023

2023

Proyecto URRA. Buenos Aires. Argentina.Grant provided by the Tomie Ohtake Institute (Brazil) and EDP Foundation.

2022

2021

︎PRIZES

2024

2022

2020

2017

45th Luiz Sacilotto Contemporary Art Salon.

Santo André. Brazil.

Santo André. Brazil.

2016

22nd Salon of Art of Anapolis.

Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis. Brazil.

Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis. Brazil.

︎SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2024

2023

2021

2021

2021

︎SELECTED EXHIBITIONS

2025

Não vou negar: Artes visuais, território e música sertaneja (I won't deny it: Visual arts, territory, and country music). Cultural Center of the Federal University of Goiás (CCUFG). Goiânia, Brazil.

COSMOS - Other Cartographies. Nara Roesler. São Paulo, Brazil.

COSMOS - Other Cartographies. Nara Roesler. São Paulo, Brazil.

2024

Tropical Delirium. Ceará Pinacoteca. Fortaleza, Brazil.

Brasilia, the art of the plateau. National Museum of the Republic. Brasília, Brazil.

The House Feels the Force of the Land It Inhabits . Cerrado Cultural. Brasília, Brazil.

The House Feels the Force of the Land It Inhabits. Cerrado Gallery. Goiânia, Brazil.

Present and Future. Museum of Contemporary Art of Goiás (MAC GO). goiânia.

The center is the insurgent west. Cerrado Gallery. Brasília, Brazil.

Brasilia, the art of democracy. Getúlio Vargas Art Foundation - FGV Art. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

New Acquisitions: Central West Collection. Antonio Sibasolly Gallery. Anápolis, Brazil.

Dos Brasis: Black Art, Black Thinking. SESC Quitandinha. Petropolis, Rio de Janeiro.

Brasilia, the art of the plateau. National Museum of the Republic. Brasília, Brazil.

The House Feels the Force of the Land It Inhabits . Cerrado Cultural. Brasília, Brazil.

The House Feels the Force of the Land It Inhabits. Cerrado Gallery. Goiânia, Brazil.

Present and Future. Museum of Contemporary Art of Goiás (MAC GO). goiânia.

The center is the insurgent west. Cerrado Gallery. Brasília, Brazil.

Brasilia, the art of democracy. Getúlio Vargas Art Foundation - FGV Art. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

New Acquisitions: Central West Collection. Antonio Sibasolly Gallery. Anápolis, Brazil.

Dos Brasis: Black Art, Black Thinking. SESC Quitandinha. Petropolis, Rio de Janeiro.

2023

Whispers from the south. LAMB Gallery. London.

Essas pessoas na sala de jantar. Eva Klabin House-Museum. Rio de Janeiro. Brazil.

Refundação. Ocupação 9 de Julho - Reocupa Gallery. São Paulo.

Dos Brasis: Black Art, Black Thinking. SESC Belenzinho. São Paulo.

Abrir Horizontes (Opening horizons). Octo Marques Cultural Center. Goiânia.

Improbable Architectures. Aura Gallery. São Paulo.

Proto-tipo. Idea!Zarvos Gallery. São Paulo.

Concretos. MUSAC - Museum of Contemporary Art of Castilla y León. León, Spain.

Complementary Opposite. AURA Gallery. São Paulo.

Essas pessoas na sala de jantar. Eva Klabin House-Museum. Rio de Janeiro. Brazil.

Refundação. Ocupação 9 de Julho - Reocupa Gallery. São Paulo.

Dos Brasis: Black Art, Black Thinking. SESC Belenzinho. São Paulo.

Abrir Horizontes (Opening horizons). Octo Marques Cultural Center. Goiânia.

Improbable Architectures. Aura Gallery. São Paulo.

Proto-tipo. Idea!Zarvos Gallery. São Paulo.

Concretos. MUSAC - Museum of Contemporary Art of Castilla y León. León, Spain.

Complementary Opposite. AURA Gallery. São Paulo.

2022

Brazilian Histories. Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP). São Paulo.

Concretos. Tenerife Espacio de las Artes (TEA). Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands. Spain.

National Art Salon of Goiás. Museum of Contemporary Art of Goiás (MAC GO). goiânia.

Contar o tempo (Counting Time). Maria Antonia University Center. University of São Paulo (USP). São Paulo.

Conversations: resistance and convergence. Contemporary Art Museum of Goiás (MAC GO). Goiânia.

Concretos. Tenerife Espacio de las Artes (TEA). Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands. Spain.

National Art Salon of Goiás. Museum of Contemporary Art of Goiás (MAC GO). goiânia.

Contar o tempo (Counting Time). Maria Antonia University Center. University of São Paulo (USP). São Paulo.

Conversations: resistance and convergence. Contemporary Art Museum of Goiás (MAC GO). Goiânia.

2021

Terra, céu e luz (Earth, sky and light). Online platform. Goiânia.

Conversations: resistance and convergence. The House of Eleven Windows. Belém.

New Acquisitions: Anápolis Artists Collection. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

Conversations: resistance and convergence. The House of Eleven Windows. Belém.

New Acquisitions: Anápolis Artists Collection. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

2020

EDP Art Award - 7th edition. Tomie Ohtake Institute. São Paulo.

Conjunto de afetos: Divino Sobral Collection. Nazareno Confaloni and Sebastião dos Reis Galleries. Goiânia

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center Rio de Janeiro (CCBB RJ). Rio de Janeiro.

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center Belo Horizonte (CCBB BH). Belo Horizonte.

Conjunto de afetos: Divino Sobral Collection. Nazareno Confaloni and Sebastião dos Reis Galleries. Goiânia

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center Rio de Janeiro (CCBB RJ). Rio de Janeiro.

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center Belo Horizonte (CCBB BH). Belo Horizonte.

2019

International Architecture Biennale of São Paulo (XII BIA). São Paulo Cultural Center (CCSP). São Paulo.

Mostra de Arte da Juventude (MAJ - Youth Art Show). SESC Ribeirão Preto. Ribeirão Preto.

44st Salon of Art of Ribeirão Preto. Museum of Art of Ribeirão Preto (MARP). Ribeirão Preto.

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center Brasília (CCBB DF). Brasília.

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center São Paulo(CCBB SP). São Paulo.

Mostra de Arte da Juventude (MAJ - Youth Art Show). SESC Ribeirão Preto. Ribeirão Preto.

44st Salon of Art of Ribeirão Preto. Museum of Art of Ribeirão Preto (MARP). Ribeirão Preto.

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center Brasília (CCBB DF). Brasília.

VAIVÉM/To-and-fro. Bank of Brazil Cultural Center São Paulo(CCBB SP). São Paulo.

2018

A body on the air ready to make some noise. Contemporary Art Museum of Goiás (MAC GO). Goiânia.

Percursos. Goiania Art Museum (MAG). Goiânia.

Dialetos II. São Paulo Cultural Center (CCSP). São Paulo.

Dialetos II. Museum of Fine Arts of Anapolis (MAPA). Anápolis.

Percursos. Goiania Art Museum (MAG). Goiânia.

Dialetos II. São Paulo Cultural Center (CCSP). São Paulo.

Dialetos II. Museum of Fine Arts of Anapolis (MAPA). Anápolis.

2017

Bordes of painting, borders of illusion. Post Office National Museum. Brasília.

42nd SARP - Salon of Art of Ribeirão Preto. Museum of Art of Ribeirão Preto (MARP). Ribeirão Preto.

45th Luiz Sacilotto Salon of Contemporary Art. Santo André.

42nd SARP - Salon of Art of Ribeirão Preto. Museum of Art of Ribeirão Preto (MARP). Ribeirão Preto.

45th Luiz Sacilotto Salon of Contemporary Art. Santo André.

2016

Convergence point. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

22nd Salon of Art of Anapolis. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

About what anybody can see now. R3 Gabinete de Arte. Goiânia.

22nd Salon of Art of Anapolis. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

About what anybody can see now. R3 Gabinete de Arte. Goiânia.

2015

Urban Hinterland. Potrich Gallery. Goiânia.

21st Salon of Art of Anápolis. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

22nd SESI Award. Frei Nazareno Confaloni Gallery. Goiânia.

TEIA. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

Strict. Museum of History of the Girona. Espain.

21st Salon of Art of Anápolis. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

22nd SESI Award. Frei Nazareno Confaloni Gallery. Goiânia.

TEIA. Antonio Sibasolly Art Gallery. Anápolis.

Strict. Museum of History of the Girona. Espain.

Texts

Divino Sobral. Cerrado Gallery. 2024.

Acclimatized Landscape / Paisagem aclimatada

Paulo Tavares. Cerrado Gallery. 2024.

Form Free Border / Forma Livre Fronteira

Alice Heeren. ARTS journal. 2023.

The Many Lives of Oscar Niemeyer’s Column: The Legacy of Brasília, Coloniality, and Heritage in the Works of Lais Myrrha and Talles Lopes

Laura Vallés Vílchez. Delfina Foundation. 2022.

Regimes of representation: interrogation and subversion.

Mateus Nunes. Select Maganize. 2022.

Brazil Builds and the possibility of a tropical modernism.

Charlene Cabral. USP (University of São Paulo). 2022.

Contar o tempo (Counting Time) exhibition.

Divino Sobral. MAPA (Museum of Plastic Arts of Anápolis). 2021.

Space, history, cartography and architecture in the work of Talles Lopes

Dora Longo Bahia. Tomie Ohtake Institute. 2020.

7th EDP Foundation Awards

Artist texts

la mappa politica dell’arte.

Interview with Talles Lopes. By Matteo Bergamini.

Art-frame Magazine.

2025.

Engolindo o Velho Mundo.

Talles Lopes .

COREIA .

2024.

Unraveling the colonial narratives of Brazilian modernist architecture in New York: “The other of the other”.

Talles Lopes.

ArchDaily.

2024.

MOMUMENAL SURPLUS

MAPA (Museum of Plastic Arts of Anápolis)

2021

SPACE, HISTORY, CARTOGRAPHY AND ARCHITECTURE IN THE WORK OF TALLES LOPES

Text by Divino Sobral

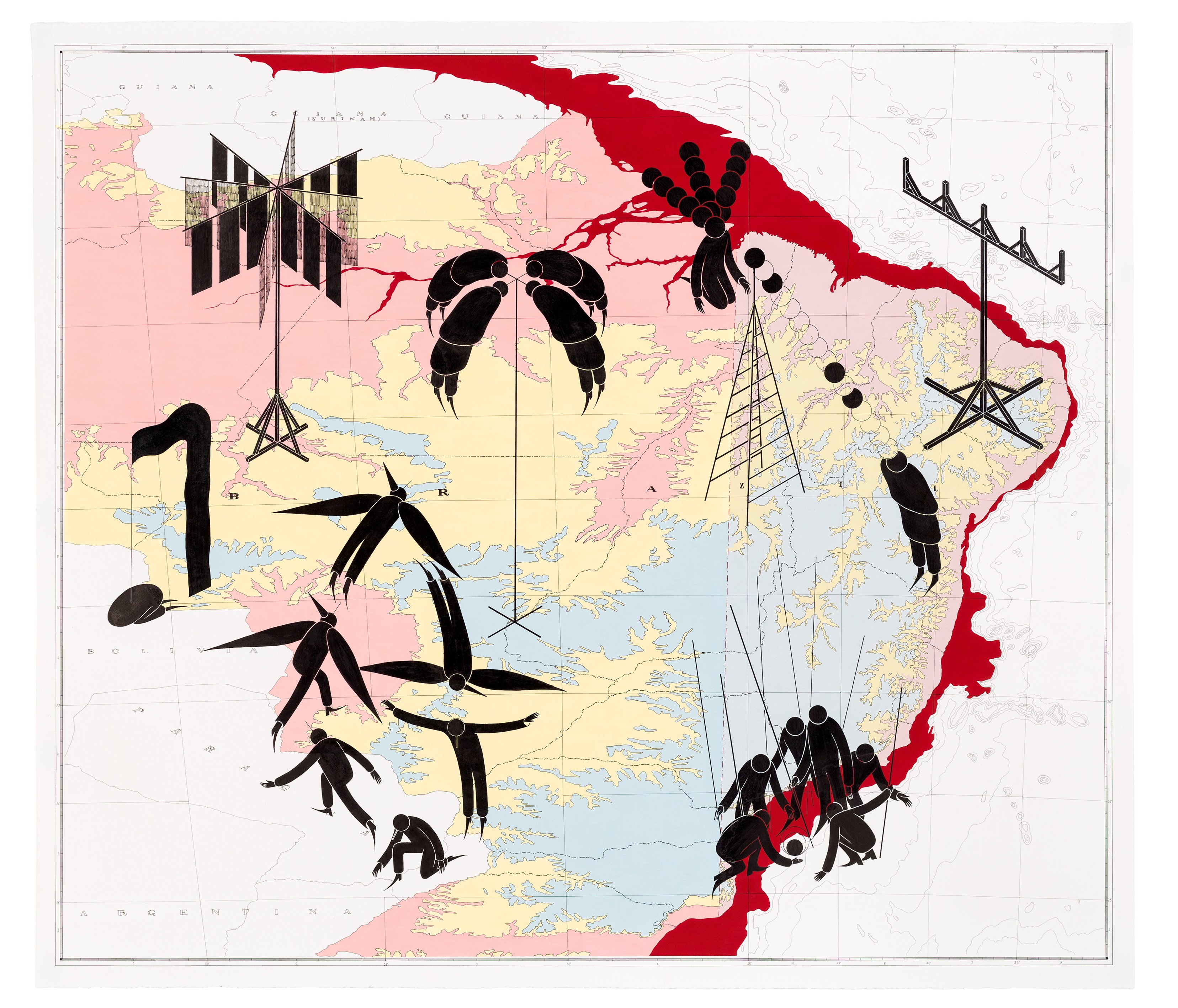

In his first solo exhibition, Talles Lopes deepens his research on space, having as major references the histories of cartography and architecture. He is an artist and researcher who delves into the layers of meanings disposed in mapping, recognition, construction, use, and representation of space, understood as a set of relationships between elements of physical and social order. His interest turns, especially, to the place where the human experience tales place, called Brazil.

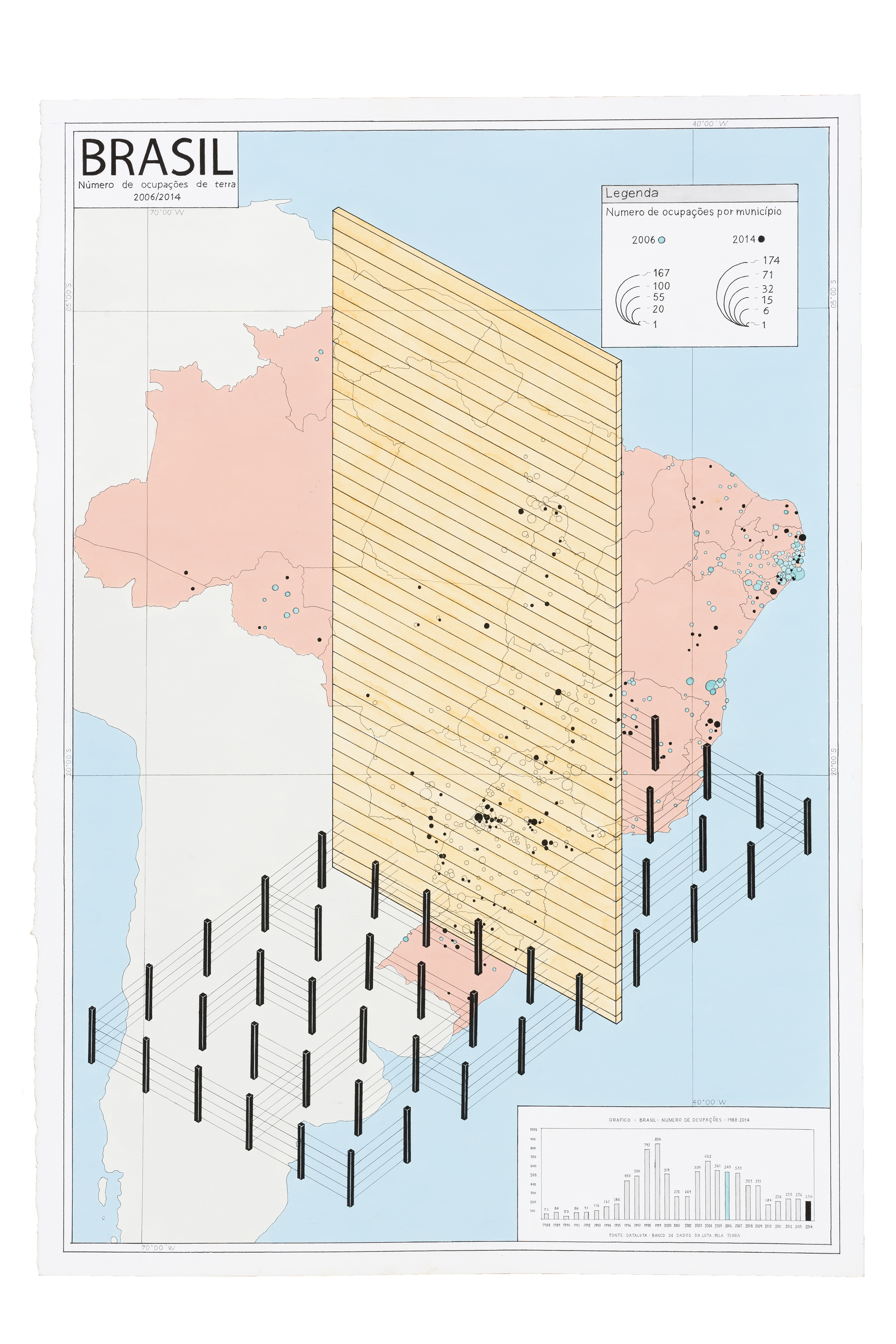

The artist problematizes the map as a visual record of space and a measurement of the actions that take place in it. He emphasizes the role of cartography both as art and as an ideological tool of control over territory, and, using cartographic conventions, comments on everything from the invention of cartographic space to actual statistical data concerning social, economic, and political issues.

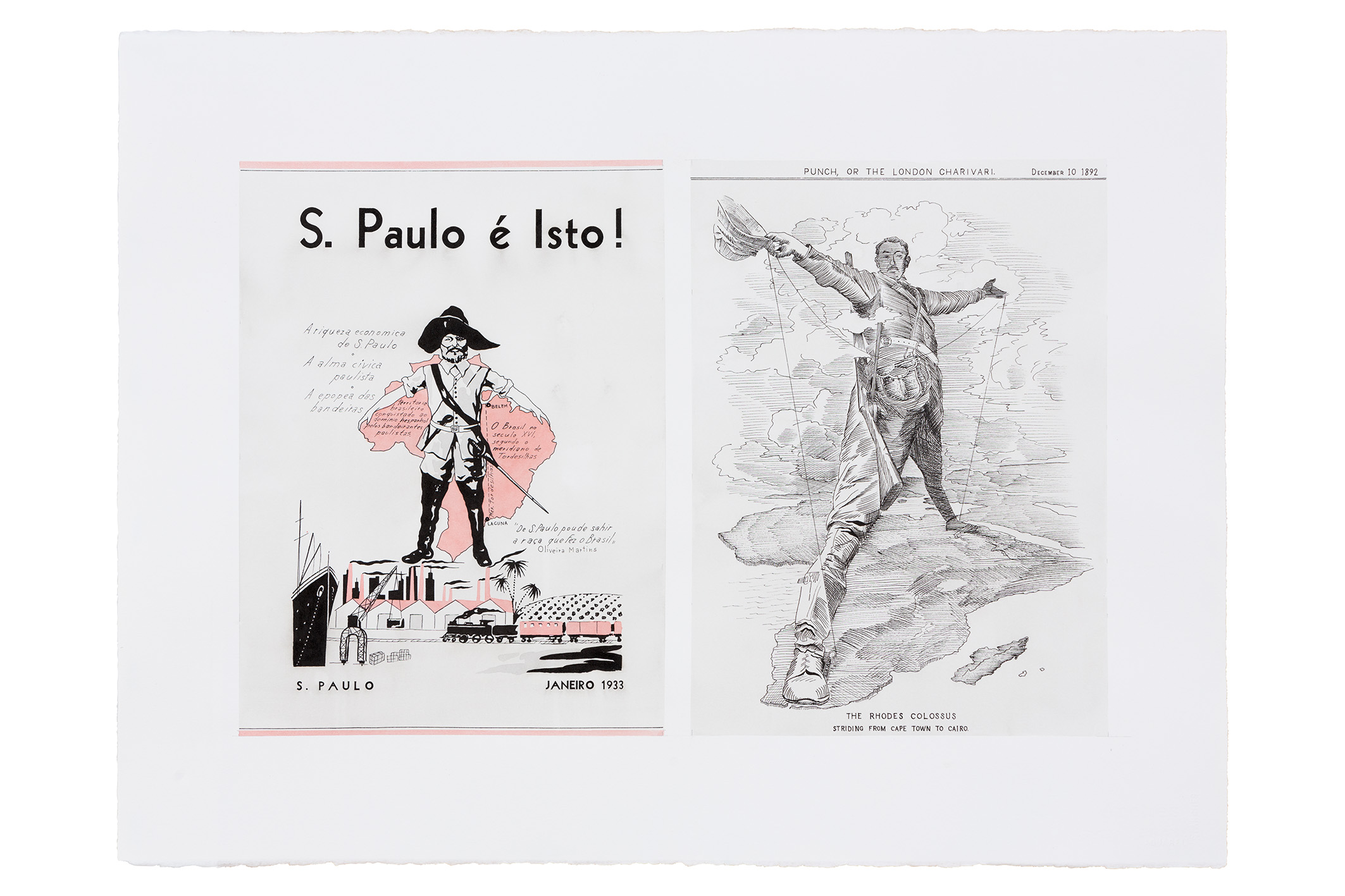

Talles Lopes reflects on the representation of the country’s interior in cartography made from the 16th century to the 1960s, and observes in the colonial maps the complete distinction between the wild interior and the civilized coast where the Portuguese invasion and colonization started; notes that the abundant mineral riches in the unknown wilderness drove the ambition of the bandeirantes (explorers), who caused the expansion of the territory at the cost of genocide; points out that the modern project of national integration and occupation of demographic voids, promoted by Getúlio Vargas with the Marcha para o Oeste (March Westward), is similar to another modernizing program of Juscelino Kubitschek, which led to the creation of Brasília in the Central Plateau.

For the artist, the production of the maps that accompanied the discourses of occupation and modernization of the Brazilian interior was updated according to the interests of each era, and remained with the same argumentation of an undominated place to be permanently occupied and explored.

In ‘A Marcha’ (2018) and ‘Mapa estriado’ (2020) he employs the Tordesillas Meridian (1494) - created by the diplomatic treaty dividing the lands belonging to Portugal and Spain on the American continent - to create from it an anamorphosis, a type of cartographic deformation that emphasizes the endless and unreachable, the always unknown Brazilian interior, which expands in an aggravated way towards the west. The result of the deformation is a representation of the monumentality of the country’s interior, and also a metaphor for the current difficulty in overcoming the permanence of the colonialist-based arguments imposed over the territory for more than five centuries.

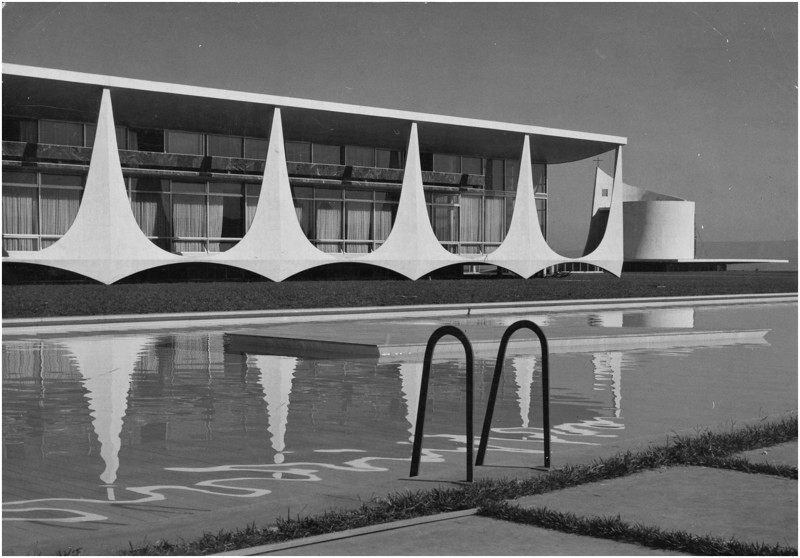

Talles Lopes criticizes monumentality as rhetoric at the service of power. The installation ‘Excedente monumental’ (2020) deals with the excess of monumentality of the architecture built in the most important public buildings of Brasília, markedly modernist. Five pieces that play at almost replicating the shape of the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), a work by architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012), are placed against the wall from one corner of the gallery. Without the care of good museography display, they are propped up and enchanted one on top of the other like surplus or remnants of what did not work out in construction.

Without the theater of power and taken to the interior of the gallery, the columns grow before the body in the same intensity in which they show themselves as parody, making fun of the great modernist architecture, they exhibit a humor that arises in large part due to the aspects of the materials used, the mason’s bill, the plaster as surface finish, and also the piled up way of displaying the pieces assumedly carnivalized.

Between quotation and appropriation, Excedente monumental either results in a scenographic architecture that criticizes the theatricality of the original column, whose unique characteristics make the opulence, elegance, lightness, grace and power of the Alvorada Palace, or reflects the presence of popular and anonymous architecture that appropriated Niemeyer’s form and recreated it in different contexts, scales, techniques and materials in Brazil.

Talles Lopes’ training as an architect is clearly shown in works dedicated to inventorying aspects of national architecture, surveying popular production created under the influence of erudite modern work through the appropriation of the canonical, in a movement that starts from the center and reaches the peripheries. This is how the artist rewrites the history of architecture in Brazil in the work constituted as a book and entitled ‘Construção Brasileira: arquitetura moderna e antiga’ (2018).

The work rehearses the catalog of the exhibition ‘Brazil builds: Architecture new and old 1652-1942’, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MOMA) in 1943. The exhibition bore the signatures of the museum’s director, architect Philip Lippincott Goodwin (1885-1958), and photographer Kidder Smith (1913-1997), who also signed the catalog, which became a reference publication on national architecture.

Following the principles of the original layout, in ‘Construção Brasileira: arquitetura moderna e antiga’ Talles Lopes recreates the publication with another narrative, inserting photographs, taken from street view, of forty buildings built in fifteen Brazilian states, which appropriate the column of the Alvorada Palace as a symbol of the modernization that reached Brazil after the second half of the 20th century.

These are residential construction projects of unknown authorship and a markedly popular nature, which make exaggerated use of the column as ornament, employing materials and colors on the order of kitsch, and thus the realm of dubious taste and provincial flavor joins the desire to demonstrate modern vision and social distinction.

In the exhibition, the book ‘Construção Brasileira: arquitetura moderna e antiga’ is displayed for public handling on a wooden shelf, affixed to the wall at the height of a base. It is placed in close proximity with two other elements: on the wall: ‘Estudo para Excedente monumental’ (2020), a watercolor representing a column of the Alvorada; ‘in space: Untitled’ (2021), a ready-made that is partly an industrial object and partly a living being, in short, a pot in which a Swiss cheese plant (Monstera deliciosa) is planted.

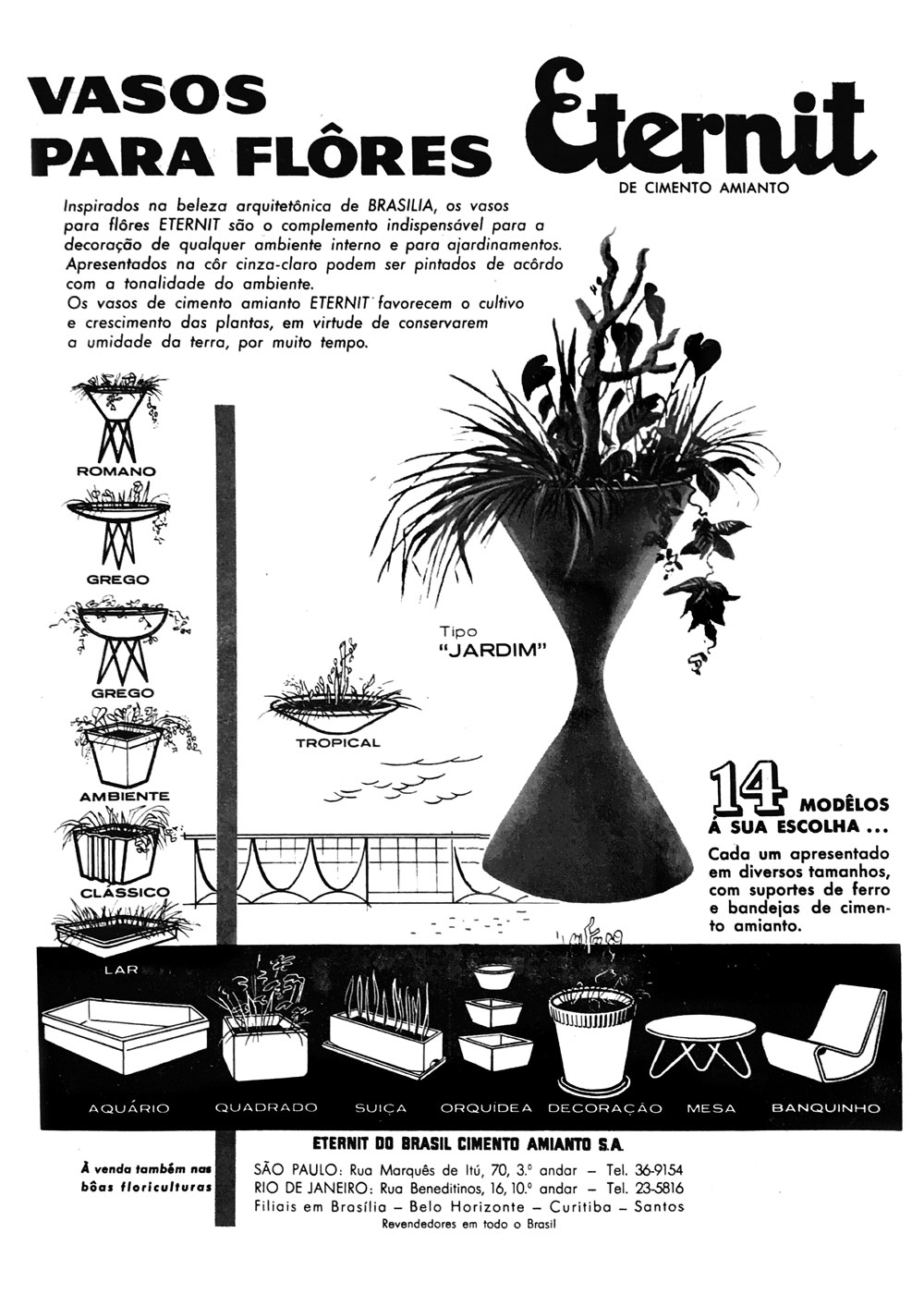

Here there is the alignment of different operations of the artist to reflect on Brazilian architecture and the ways of presenting it. Situated as a ready-made, the vase appropriated by Talles Lopes is signed by Willy Guhl (1915-2004), Swiss architect and designer, member of the neo-functionalist movement that worked focused on the research of new materials during the reconstruction of Europe after the Second World War. The round model used by the artist is part of a series of vases with modernist lines created in the early 1950s for the Swiss company Eternit and produced with a mixture of concrete and asbestos. Guhl’s vases were also manufactured in Brazil and began to accompany the modernization of the domestic landscape of the middle classes.

Exuberant and very plastic, the Swiss cheese plant (Monstera deliciosa) was part of the list of ornamental plants that were exhibited among photographs, houseplants and models, in the exhibition ‘Brazil builds: Architecture new and old 1652-1942’. With this operation, Talles Lopes resumes MOMA’s expographic proposal of putting in dialogue modernist architecture and tropical landscape, while reaffirming Guhl’s intervention in Brazilian gardening. It is necessary to note that native plants only had their plastic potential for landscaping recognized and used in the second half of the 1930s. Previously the taste for exotic, mainly European, species predominated.

Landscape is one of the genres Talles Lopes uses to think about and approach the modernization of space resulting from technical development, economic progress, and the installation of the new as a strategy to overcome the old. He investigates landscapes in inland and distant places in Brazil, marked by isolation and backwardness, dominated by buildings that somehow reproduce the canonical form of modernist architecture, the column of the Alvorada Palace, symbol of modern Brazil turned towards progress and the future embedded in the popular imagination after the construction of Brasília.

Executed from a street view photograph that has peculiar distortions, made with a historical painting scale, the imposing painting ‘Clube Belavistense’ (2021) depicts a landscape of Bela Vista, a small town on the border of Mato Grosso do Sul with Paraguay, and focuses on the strange construction raised on the corner of two streets of pitted asphalt; exceptional for the context around it, the construction draws attention by the size of its built area and by the presence of an architectural design that cites the Alvorada column. On the distant border it displays to the neighboring country the sign of modernity intended for all the country’s borders.

‘The great waterfront of Novo Aripuanã’ (2020) is an installation composed of two elements: a painting representing the landscape of the port city of Novo Aripuanã, on the banks of the Madeira River, in Amazonas; a wooden replica of a bench in a square in the city of Três Lagoas, in Mato Grosso do Sul. Both address the appropriation of the Alvorada column by official constructions, linked to the municipal sphere. There is in the architecture of the port a mention of the patriotism typical of the period of the Military Dictatorship, expressed in the façade where one can read “We love Brazil”.

The small bench positioned in the space in front of the painting contemplates the harbor landscape. In this work, very distinct Brazils, the Amazon and South Mato Grosso interiors converse quite closely as they replicate the same icon of modernity. Through this installation, Talles Lopes thinks the unity and diversity of Brazil, and simultaneously calls up the different histories of its occupation, its construction, and its modernization.

Goiânia, October 2021

Brazil Builds and the possibility of a tropical modernism

Talles

Lopes questions the attempt to establish a modern-country project through

Brazilian architecture

By Mateus Nunes

Brazil Builds (2022), by Talles Lopes. Contar o tempo (Counting Time) exhibition. [Photo: Charlene Cabral]

Text originally published in Portuguese, on the Brazilian art magazine seLecT, in July 12th, 2022 [link].

Mateus Nunes is a writer, curator and researcher. Holds a PhD in Art History from Universidade de Lisboa (Lisbon, Portugal) and a BA in Architecture and Urbanism from Universidade Federal do Pará (Belém, Brazil). Guest Lecturer at Universidade de São Paulo (Brazil) and Professor at Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Brazil).

The Brazilian artist Talles Lopes, in his installationBrazil Builds (“Construção Brasileira”, in Portuguese) (2022), revisits Brazilian iconography and a photographic architectural tradition linked to a project to modernize the nation. Composed of printed and diagrammed photos on a metallic structure that combines orthogonal and curved elements, the installation also has a set of asbestos vases with plants commonly used in modern landscape projects in Brazil. The visual artist, graduated in Architecture and Urbanism from Universidade Estadual de Goiás, in 2020, recently joined the Delfina Foundation residency program, in London, with the support of the Inclusartiz Institute, and presented Brazil Builds at the group exhibition Contar o Tempo, at Centro Culturam MariAntonia (São Paulo, Brazil), in 2022.

The exhibition was structured around provocative and inquiring premises about the thought of time, based on the transdisciplinary arsenal available to tackle the problem in contemporary times, in addition to events that propose a review of the counting of that time in Brazil, such as the country's Bicentennial of Independence, and the Centenary of its Week of Modern Art (“Semana de Arte Moderna”), at Theatro Municipal, in São Paulo. The group exhibition brought together works by Adriana Moreno and Marina Zilbersztejn, Aline Motta, Carmela Gross, Clara Ianni, Diogo de Moraes, Dora Longo Bahia, Elilson, João Carlos Moreno de Sousa, Laís Myrrha, Marilá Dardot, Marcelo Moscheta, Rosana Paulino, Walmor Corrêa and the MAE USP Archaeological Center.

In the photos displayed in the installation, Lopes presents reverberations – or reappearances – of the characteristic columns that compose the main facade of the Palácio da Alvorada, in Brasília, designed by Oscar Niemeyer for the official residence of the presidency of the Republic of Brazil – in addition to being the first construction of reinforced concrete officially inaugurated in Brasília, in 1958. These elements, in the buildings researched by Lopes, reappear in colonnades of porches, balconies and marquises, balustrades and in ornaments applied or painted on external facade walls of what is read by a popular and non-erudite architectural expression – although clearly knowledgeable and attentive to important academicist architectural achievements.

The integration of these elements – which have become iconic in Brazilian architecture, in the order of the canon or the treatise – in popular buildings demonstrates a kind of development of a tropical civilization, accentuating the discrepancies between the Eurocentric attempts of a modernist enterprise around the world and the effective unfolding of this project of modernity in the tropics. The reception – and operation – of these foreign traditions follow one another like a second wave coming to Brazil across the Atlantic, following in due proportions the first colonialist onslaught in the 16th century.

In his solid research, the artist collects photos through bibliographic and digital research, by receiving photos sent by people familiar with Lopes' research, and by photographs taken by the artist himself, mapping dozens of buildings that replicate the column in the five major Brazilian geographical regions. This image bank fuels – and haunts – Lopes' research in recent years. In the installation Brazil Builds, the artist chooses to present only photographs from Google Street View, intensifying the friction between images of different natures: a modern international, sold abroad by Brazil and vice versa; a local one, materialized in Brazilian streets; and a digital and globally connected one, guided by the dynamics also imported from a surveillance policy.

The photographs shown in the installation present an effective Brazilian construction, culturally hybrid, in an imagetical fusion between the tradition considered “erudite” and the popular practice. They revisit canonical symbols in architectural culture in a non-academicist way, incorporating these ostentatious marks of modernity in unofficial buildings. The artist makes the photos displayed in the installation have visual aspects similar to those that were part of the exhibition Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old, 1652-1942, from 1943, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), provocatively alluding to an artificial construction of history.

Photos

from the Brazil Builds exhibition at MoMA NY (1943).

Source: MoMA

Source: MoMA

The modern historiographical project imposed on Brazil privileged, through photography, the imagery display of a narrative construction that, at the same time that showed the solidity of the architectural traditions of certain countries, used this framework as a justification for the implementation of a project of modernity. Brazil, therefore, with “four centuries of history”, would be able to live a new phase in its civilization. In this way, photography was used not only as a symbol of modernity, but as an effective and easy institutional dissemination vehicle around the world of what supposedly happened in modern Brazil.

In addition to presenting the photos in a way similar to that shown in the historic exhibition Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old, 1652-1942, from 1943, at MoMA, the artist uses the same typography in his work that tops the structure of the expography of the Brazilian Pavilion atExpo 58 (Brussels World's Fair in 1958). The official translation of Brazil Builds into Portuguese resulted in the name Construção Brasileira, which Lopes uses as the Portuguese title of his installation. In this work, the artist continues to use the citation of these historical events as a review tool: he also recreates the expographic project of the Brazilian pavilion of Expo 58, designed by architect Sergio Bernardes, which featured the column of Palácio da Alvorada – designed by Oscar Niemeyer – for the first time in a European exhibition.

George Everard Kidder Smith, responsible for most of the photographs shown in the exhibition and in the Brazil Builds’s catalog at MoMA, was an American architectural photographer, with a solid production on modernist architectural development in countries such as Sweden, Italy and Switzerland – to the Stockholm Builds exhibition, also at the MoMa (1941); and for the publications Switzerland Builds – Its Native and Modern Architecture (1950) and Italy Builds: Its Modern Architecture and Native Inheritance (1955), respectively. He was the author of Source Book of American Architecture: 500 Notable Buildings from the 10th Century to the Present, originally published in 1981, a kind of imagery compendium of buildings in the United States. It can be seen that the thinking, not only of Kidder Smith, but of other institutional protagonists of his time — such as Philip L. Goodwin, board member and curator of MoMA — sought to portray the modernization of different countries through architecture, incorporating – albeit narrowly – local specificities. Goodwin and Kidder Smith led the organization of the Brazil Builds exhibition in 1943.

Seaplane station, Areroporto Santos Dumont, Rio de Janeiro, Atilio Corrêa Lima, architect, 1940, photo by George Everald Kidder Smith in the catalog for the exhibition Brazil Builds (1943) at MoMA NY (page 151)

Lopes' work allows us to rethink the temporal arc established by the remarkable 1943 exhibition – which proposed a cut from 1652 to 1942 – and by its subtitle, which decreed that Brazilian architectural culture only began in the 17th century. This chronological section reiterates a colonialist view that despises the cultural, artistic and architectural traditions of the native peoples of Brazilian territory before the Portuguese invasion. The very modus operandi of photographer Kidder Smith, according to historian Robert Elwall, followed a classic speed of traveling artists and naturalists who, coming from abroad, sought to portray the fauna, flora, geography and people of Brazil in a vertiginous way, without paying attention to the heterogeneous Brazilian complexities. It even shares an ethnographic approach on photography, by portraying the territory of the other, as Felipe Augusto Fidanza and Pierre Verger did. Studies that share decolonial matrices – such as Brazil Builds, by Lopes – provide critical reviews regarding the temporal and evolutionary historiographical understanding, an epistemological model of European origin, which defends a linear accumulation of knowledge throughout history that would lead modern Western society to be more and more evolved.

Lopes aims to present a trustworthy Brazilian genealogy of the architecture of his country, which builds in a non-erudite way, replicates fads that serve as imagetic and social distinctions and brings together the erudite and the popular in an inseparable amalgam, rooted in the country's history. Would the history of Brazil begin, then, with the construction of the pillars of Palácio da Alvorada? This trans-historical vertigo is even purposely made by Lopes: the columns of the Palácio do Alvorada were built between 1957 and 1958, therefore outside the temporal arc delimited by the Brazil Builds exhibition, which included buildings until 1942. This confusion reaffirms the ineffectiveness of modern and positivist chronological models to analyze Brazilian cultural complexities, in addition to criticizing the establishment of stereotyped visual narratives based on a narrow exoticism linked to Brazil.

How to combine the potential for modern development with the exuberance and grandeur of Brazilian fauna? How to deal with this monumental and ornamental surplus – the name with which Lopes wisely baptized his work Monumental Surplus (“Excedente Monumental”), from 2022? Did Brazilian architecture propose a fusion between structure and ornament? Is the modern development plan concerned with sustainability and with the disposal of solid waste from its constructions, a problem that has long been resolved by Brazilian indigenous populations in their highly sustainable construction techniques? What, therefore, would sustainable development be if not a return to the understanding and time of the country's history, and not an incentive to promote modern industry? Lopes' work engenders, in multiple and rhizomatic questions, the shuffling of a history established as official with narratives always on the margins of historiography. In this way, a Brazilian imagery system is built based on historical colonialism, modernism and popular constructive practices, reiterating a hybrid Brazil.

In the Brazilian Builds installation, Lopes has several asbestos cement vases, designed by the Swiss designer Willy Guhl and produced in Brazil by the Eternit company. In the vases, the artist displays specimens of plants widely used in modern landscaping, in an operation of citation to the vegetation used in important publications and exhibitions of the time on modern architecture – such as Philodendron Burle Marx, peace lily, white anthurium and syngonium, used in the Brazil Buildsexhibition at MoMA, as possible props for a Brazilian flora.

Monumental Surplus (2021), by Talles Lopes [Photo: Ricardo Miyada]

The vases, with the shapes of parabolas, hyperbolas and rectangular prisms, suspended by discreet metallic supports, align themselves with the sinuosity and formal austerity of the aesthetic proposals for the architecture of Brasília. The images advertising the sale of this family of vases in Brazil present sketches of the facade of the Palácio da Alvorada in the background, with models whose names range from “Roman”, “Greek” and “Switzerland” to “ambient” and “tropical”. Creating a friction concerning the sinuosity of the curved line without necessarily entering into discussions about ornament in Brazilian modern architecture is one of the multiple issues engendered by Lopes in the installation.

Asbestos, a chemical component used in the construction of this type of vases and in an extensive range of civil construction products, was banned from trade in Brazil as of 2017, due to its high carcinogenic toxicity when inhaled. Therefore, we rethink how toxic are the practices linked to a hurried, forced modernity, based on unsustainable industrial production and extractive natural resource management. Subjecting themselves to practices of this nature can lead us to consider the price that these countries were willing to pay to implement an imported and harmful project of modernity in their structure.

How long will we repeat a problematic tradition, imagery and materially? The idea of “Brazil, a country of the future”, title of the book by Stefan Zweig originally published in 1941, and the idea that “Brazil has a huge past ahead of it”, as Millôr Fernandes claimed, clash. To understand the modern Brazilian architectural culture is to realize that decadence and development go hand in hand. Zweig defended Brazil as a land where civilization could develop peacefully after the traumas and blemishes of the Second World War, just as the European colonists found in Brazil, in the 16th century, their “New World”, and how the Brazilian government and the great extractive industries found in the Amazon pure developmental potential. Brazil is always a land of promise of dreams, gradually exhausted.

Lopes' work allows us to reflect on the oscillating and rhizomatic dynamics of the irradiating poles of artistic models, demonstrating that places can behave as a center and as a periphery at the same time, portraying an ambiguity inherent to contemporaneity and post-colonial dynamics. Brasília, for example, from a positivist and modern perspective, would be in a position on the periphery in relation to Europe, the center that established the guidelines that guided architectural modernism in a hegemonic way. At the same time, however, Brasília also established itself as a center, by radiating models resulting from Brazilian modern architecture to other cities that absorbed them. The images and aesthetic systems therefore cross the capital of Brazil, without being left unscathed by the operations and pluralities made in this movement, causing an untraceable reverberation that diffuses these images in a capillary way, at the same time that it receives them. This tug of war that pulls in both directions at the same time illustrates the cultural hybridisms that have guided Brazilian cultural production for centuries, without forgetting to denounce the imposition – sometimes subtle, other times wide open – of a Eurocentric ideological and iconological violence.

7th EDP Foundation Award.

Tomie Ohtake Institute. By Dora Longo Bahia

2020

Text originally published in the catalog of the 7th EDP Foundation Award. 2020. Instituto Tomie Ohtake. Sao Paulo, Brazil.Jury composed by Amanda Carneiro, Arthur Chaves, Dora Longo Bahia, Elilson and Theo Monteiro.

...

that all great world-historic facts and

personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add:

the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

Karl Marx[1]

personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add:

the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

Karl Marx[1]

1960 - Tragedy. Brazil's new capital city is dedicated as part of the on-going project of occupation and domination dating from colonial times, in the 16th century. The “modern palaces” — Planalto[presidential headquarters] and Alvorada[presidential residence] - were built on foundations drawn from Portuguese-tropical colonial mythology. Their architecture repeats the horizontality of the plantation estate homes with their wide porches or verandas, surrounded by a teeming vegetation and guarded by uniformed henchmen.[2] The alleged modernity was structured on the tragedy of underdevelopment and dependence, evincing the absolute prerogatives and privileges of the mighty landowners.

The design of Brasília picked up on a perverse process of “domestic colonization,” conveyed by the installation of military barracks all along what is known as the city's monumental axis. Why have barracks within the city limits? What would be the specific functions of these troops, when the “New Capital” was geographically protected [in Brazil's central plateau] from an unexpected enemy attack? The only plausible justification was that these troops were not meant to defend the nation against foreign enemies, but rather to parade their military apparatus along the monumental axis of the city, “to make an impact on the residents and to weigh [...] on the deliberation of one or more powers of the Republic. But then why relocate the capital? Why Brasília? Why dream about utopias?”.[3]

2020 - A farce. President Jair Messias Bolsonaro has been in office for nearly two years. Supported by the imperialist United States, the double articulation - external dependence and social segregation - has been definitively set as a basic foundation for the accumulation of capital.[4] The fascist counterrevolution topples not only the developmentalist ideas of the construction of Brasília but also the socialista dreams of some of its designers, to the shouts of an antisocial, anti-national and anti-democratic society. Poverty, misery, and death have been definitively turned into the Brazilian elite's goose that lays the golden eggs. The Army once again is brought to bear against those it should protect, and the president's hidden uniform becomes increasingly visible. There is no illusion that civilized capitalism could be on its way. The veil of modern utopia has been definitively removed, revealing the precarious and farcical structures it was hiding.

And so what? Haven't we stopped dreaming about utopias for some time now? Hasn't national politics always been obscene? What is the reason for this somewhat gloomy text in a catalogue of an exhibition of works by young artists?

Beware! Transported from the mythic Brazilian West by Talles Lopes, the farce of Brasilia's utopian modernism has come to haunt this exhibition.

Dora Longo Bahia

07.09.2020

[1] MARX, Karl. “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte”. In: ADORNO, Theodor W. Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords. Henry W. Pickford (Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, p. 388.

[2] The art historian Luiz Renato Martins quoted Niemeyer having stated at that time: “The Palace of the Dawn [...] suggests elements from the past - the horizontal order of the façade, the wide verandas that | designed with the aim of protecting this palace, the little chapel rounding out the complex as a recollection from our old plantation estate homes.” (NIEMEYER, Oscar. “Depoimento.” Revista Módulo, Rio de Janeiro, no. 9, pp. 3-6, Feb. 1958, cited in MARTINS, Luiz Renato. “Pampulha e Brasília, ou as longas raízes do formalismo no Brasil.” Crítica Marxista, no. 33, pp. 105-114, 2011. Our translation. Available in Portuguese at: https://www.ifch.unicamp.br/criticamarxista/arquivos_biblioteca/artigo242merged_document_252.pdf).

[3] In 1957, art critic Mário Pedrosa already noted that “something contradictory is hidden in the very modern wrapper of the conception” of Brasília, comparing the capital to Maracangalha, the Bahia district immortalized by Dorival Caymmi, and questioning about what in fact was in play in the moving of the capital to the country's Center-West (PEDROSA, Mário. “Reflexões em torno da nova capital.” In: ARANTES, Otília B. F. (ed.). Acadêmicos e modernos: textos escolhidos, v. Ill. São Paulo: Edusp, 1995, pp. 394-401, cited in MARTINS, 2011).

[4] Cf. SAMPAIO JR., Plínio de A. “Desenvolvimentismo e neodesenvolvimentismo: tragédia e farsa.” Serviço Social & Sociedade, São Paulo: Cortez, no. 112, Oct./Dec. 2012. Available at: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-66282012000400004.

Talles Lopes

By Charlene Cabral

Critical text written for the exhibition Contar o tempo. 2022.

Curated by Dária Jaremchuk at the Maria Antônia University Center.

USP - University of São Paulo.

Being the stage in which the sun has already surpassed the horizon line, the dawn can be defined as the beginning of the day itself, and the instant preceded by the aurora, which is the light seen before the sun rises. Notice the subtle difference: between the aurora and the dawn, only a few minutes, and the poetic possibility of assigning to the former a certain dose of hope, for what it announces, and of mystery, for what it does not make evident; whereas the latter is an ongoing situation, visible, with more explicit stages. In this one, the origin of the name Palácio da Alvorada (“Palace of the Dawn”, in English), Oscar Niemeyer’s design for the Brazilian president’s official residence, the first masonry work inaugurated in Brasília, in 1958, amidst the expansionist project euphoria.

It would have been much more humble to name the Palace through the bias of hope and mystery than to name it through the visible achievements - most importantly because these achievements began symbolically with itself -, but the design of Brasília was exactly that: the embodiment of an idea, a dream of progress, with no place to nuances or the absence of certainty. And architecture, as in so many other times in human history, would outstandingly accomplish its role of the power’s spectacular portfolio, whichever was the position in the ideological and political spectrum of the individuals involved in the planning of these emblematic buildings or their future inhabitants. From this dawn, a shared bet on the future of the country was born.

In the same year, the Brazilian Pavillion was presented at the International Exhibition in Brussels, showing a model of modern tropical civilization, in which the building of Brasília was in the spotlight and a big picture of the Palácio da Alvorada was shown to the world.

Graduated in Architecture, Talles Lopes lined this and other symbolic episodes in the presentation of the work Brazil Builds” (2022), an installation composed of a big metallic panel with black and white pictures, accompanied by a garden with usual plants in Brazilian landscaping. The species are planted in asbestos concrete vases from the 1960s, designed by the Swiss designer Willy Guhl and made by the company Eternit in Brazil. According to the advertisement from that time - also exposed in Lopes’ panel - these vases were inspired by the “architectural beauty of Brasília”, and, indeed, their clean and sinuous shapes, balancing weight and lightness, enable a visual relation with the modernist design. The material, very resistant and flexible, widely used as raw material in construction throughout the 20th Century, is nowadays forbidden in Brazil and many other countries for being highly harmful when inhaled. At this moment, if desired, a dark metaphor about the euphorias that concern certain ways of producing development can be added.

Lopes is an artist born in 1997 who since 2015 - thus rather young - has been placing himself into the art system through awards, such as Prêmio EDP nas Artes (Tomie Ohtake Institute), and through taking part in exhibitions such as the São Paulo International Architecture Biennial (CCSP) and Vaivém, curated by Raphael Fonseca at Banco do Brasil Cultural Center, amongst many others. Most recently, he held the individual exhibitions Excendente Monumental (“Monumental Excedent”, in English) at Museu de Arte de Anápolis - MAPA (Anápolis Art Museum), and Colonial Oasis at C.A.M.A., a showcase organized by the Portuguese gallery Kubik Gallery in the capital of São Paulo. At the time these lines are being written, he is a resident at Delfina Foundation in London and already has other participations in line over the year.

His career has been coherent not only in terms of placement but also, overall, in terms of the conceptual and aesthetic outcomes of his works. The design, in the architectural sense, is the support of his production, and from there Talles Lopes works solutions out. His “Sem Título” (“No Title”, in English) (2015-2018) map series, in which he uses gouache, watercolor, acrylics, and ink on paper, achieving a clean and precise result, unfolds the possibilities of the cartographic drawing, adding images and other composition elements that require an interpretative will from the spectator, at the same time they put themselves into an intuitive exam or, to the less restless, purely visual. In these works, the mastery of his lines is evident; that is just the beginning, though.

In his most recent works, the designformat shows up in an even more evident way. The drawing is still the foundation but behind the main scene. The pieces are signed by different collaborators, in many distinct raw materials, that are always credited in the technical specifications of the pieces. In some cases, the performer presumably literally executes the project, as in the structures; in other cases, it is indeed a commission: Talles Lopes counts on the lines of the person that has been hired, as seen in the large size paintings that compose A Grande Orla de Novo Aripuanã (“Novo Aripuanã’s Great Waterfront”, in English) (2020), made by Valdson Ramos, based in Lopes’ design for the Goiás Museum of Contemporary Art’s span (2018), made by Jaime Pureza.

This scrambling logic in authorship permeates his production, which does not change in Construção Brasileira - in both the photobook from 2018 and its unfoldings and in the installation presented in “Contar o tempo” (“Counting time”, in English). Here, the pillars from Palácio da Alvorada are once again the main element. The artist has been thinking about this element and unfolding it every other time throughout his path. A few years ago he started to collect images of vernacular buildings spread all over Brazil, where the modernist pillar comes up as an ornament on the façades of these buildings. It is clear the many kinds of quotations, replicas, or tributes that have certainly not been expected by the celebrated Oscar Niemeyer. A further and not-planned stage of this dawn that seems to never finish beginning.

Despite being born in Guarujá (in the coastal area of São Paulo), Talles Lopes was brought up and still lives in the Brazilian midwestern region, in the city of Anápolis, located approximately 140km from the federal capital and strategic point for transshipment during the building of Brasília. That is from where he has been visiting buildings scattered all over the inner parts of the Brazilian states, in a sort of architectural mapping. With a method that gathers the search of keywords on social platforms, consulting literature on popular architecture, long toursthrough Wikipedia and Google Street View, and pictures sent by acquaintances, he has already mapped more than 60 buildings that recreate the pillar, not only in the central region of Brazil but also in states such as Acre, Rio Grande do Sul, Amazonas, and Paraíba. Putting together such a collection, it does not make any difference if Lopes has been to these places in person or not, once the traveling artist is always an outsider; it also does not matter if he was the one to take the pictures or not. The main point in a work like this one is the statement he produces when he decides to present them all together under the same black and white aesthetics, emulating a vision from the past, even though it is clear these images have been taken from Google since they show their typical distortions, watermarks or shadows.

A collection that points thus to the frictions between copyright architecture (rare, distinct, exclusive) and ordinary architecture (common, banal, unrestricted), motivating thoughts on the ways of popular assimilation of visualities connected to power or the spectacular, and also of its subversions, voluntary or not. In addition to that, it allows us to reflect upon the official (or officious) historical speeches and the role of the images in both their reaffirmation and scrambling, resulting in a research that is capable of informing and exposing certain margins of a national map essentially centralized and therefore unknown.

Delfina Foundation

Artistic Residency carried out with the support of the Inclusartiz Institute (Brazil).2022

During my residency at Delfina Foundation (2022) in London, I dedicated myself to investigating a specific question that has been permeating my work for some time now: how did the Brazilian modernist program update and perpetuate narratives that befit the colonial heritages in Brazil, from buildings to its public debating platforms (such as publications and exhibitions)?

Thus, during the residency, I chose to research catalogs and archives of exhibitions that proposed to present the modernist production of Brazilian architecture to the global north in the mid-twentieth century. Searching collections such as Tate Britain, The National Archives, Whitechapel Gallery, RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and the Embassy of Brazil, archives of exhibitions such as Modern Brazilian Paintings (Royal Academy. 1943), Brasilia: the building of a new capital for Brazil (ICA London/1958), among others.

In this process, from the contact with the iconic image of a palm tree on the cover of the catalog of Brasilia: the building of a new capital for Brazil (1958), I turned my investigation to thinking about the relationship that vegetation established with architecture in publications and exhibition spaces. When visiting the images of

Brazilian pavilion at EXPO 58 (Brussels, 1958) available in the RIBA library archive, I paid attention to the way in which tropical plants competed with architectural photographs in the pavilion.

In parallel, after having contact with the research around the project "The Art of Diplomacy - Brazilian Modernism Painted for War", 2018, (investigation carried out by the Brazilian Embassy in London on the legacies in the UK of the exhibition Modern Brazilian Paintings, 1944), I identified that London had received from MoMA a series of architectural photographs previously presented in Brazil Builds (MoMA. New York, 1943). I returned to thinking about the relationship between these images and the vegetation in that first exhibition in New York, paying attention to the fact that the plants were presented on exhibition displays as well as the models, leaving the purely ornamental field to be inserted as an object of the exhibition.

The astonishing presence of a series of exotic vegetations in the global North, in exhibitions that proposed, fundamentally, to recount an idea of “Brazil”, seem to clash with the images of the transformations that were going on through that period in the country, such as the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the inner parts of Brazil and the progress of huge construction works like the Belém-Brasília highway.

Thus, the appropriation of tropical plants at these exhibitions would be symptomatic of the neocolonial dynamics in Brazil at that time. Considering the fetish for the domestication of such species inside the planned spaces of modernist architecture, the argument of domination over anything or anyone considered savage was veiled. Perhaps those exhibition spaces tried to simulate the logic of the acclimatization gardens in Europe (Like Kew Botanical Gardens or the classic Crystal Palace), structures that not only adapted tropical species to the European cold weather but also symbolized the vast colonial domination through the diversity of species extracted from several territories. The Brazil which strived to adapt the modernist repertoire to the tropics also tried to come out as the Brazil capable of articulating its own acclimatization garden with species from its own territory, as a symbol of its auto-colonial corporation.

In this sense, during my period at Delfina, I began to study a possible subtraction of the architectural references present in the photographic records of these exhibitions without intervening in the presence of vegetation in the spaces, trying to delineate how the presence of these elements occurs not as an exhibition arbitrariness, but as an element central to the maintenance of a given narrative. This process has led to a series of works, including Brazil builds (2022) and Acclimatization Garden (2022).

Thus, during the residency, I chose to research catalogs and archives of exhibitions that proposed to present the modernist production of Brazilian architecture to the global north in the mid-twentieth century. Searching collections such as Tate Britain, The National Archives, Whitechapel Gallery, RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and the Embassy of Brazil, archives of exhibitions such as Modern Brazilian Paintings (Royal Academy. 1943), Brasilia: the building of a new capital for Brazil (ICA London/1958), among others.

Brasilia: the building of a new capital for Brazil” (ICA London/1958). Source: Tate Archive

Modern Brazilian Paintings (1944)

Modern Brazilian Paintings (1944)

Visit to the archives of the Brazilian Embassy. 2022

In this process, from the contact with the iconic image of a palm tree on the cover of the catalog of Brasilia: the building of a new capital for Brazil (1958), I turned my investigation to thinking about the relationship that vegetation established with architecture in publications and exhibition spaces. When visiting the images of

Brazilian pavilion at EXPO 58 (Brussels, 1958) available in the RIBA library archive, I paid attention to the way in which tropical plants competed with architectural photographs in the pavilion.

In parallel, after having contact with the research around the project "The Art of Diplomacy - Brazilian Modernism Painted for War", 2018, (investigation carried out by the Brazilian Embassy in London on the legacies in the UK of the exhibition Modern Brazilian Paintings, 1944), I identified that London had received from MoMA a series of architectural photographs previously presented in Brazil Builds (MoMA. New York, 1943). I returned to thinking about the relationship between these images and the vegetation in that first exhibition in New York, paying attention to the fact that the plants were presented on exhibition displays as well as the models, leaving the purely ornamental field to be inserted as an object of the exhibition.

The astonishing presence of a series of exotic vegetations in the global North, in exhibitions that proposed, fundamentally, to recount an idea of “Brazil”, seem to clash with the images of the transformations that were going on through that period in the country, such as the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the inner parts of Brazil and the progress of huge construction works like the Belém-Brasília highway.

Brazilian pavilion at EXPO 58 (Brussels, 1958). Source: RIBA

Crystal Palace. Hyde Park. 1852. Source: Victoria and Albert museum

President JK knocking down a gigantic jatobá tree over 50 meters high in a symbolic act for the completion of the Belém-Brasília highway. 1959. Source: National Archive of Brazil.

Thus, the appropriation of tropical plants at these exhibitions would be symptomatic of the neocolonial dynamics in Brazil at that time. Considering the fetish for the domestication of such species inside the planned spaces of modernist architecture, the argument of domination over anything or anyone considered savage was veiled. Perhaps those exhibition spaces tried to simulate the logic of the acclimatization gardens in Europe (Like Kew Botanical Gardens or the classic Crystal Palace), structures that not only adapted tropical species to the European cold weather but also symbolized the vast colonial domination through the diversity of species extracted from several territories. The Brazil which strived to adapt the modernist repertoire to the tropics also tried to come out as the Brazil capable of articulating its own acclimatization garden with species from its own territory, as a symbol of its auto-colonial corporation.

In this sense, during my period at Delfina, I began to study a possible subtraction of the architectural references present in the photographic records of these exhibitions without intervening in the presence of vegetation in the spaces, trying to delineate how the presence of these elements occurs not as an exhibition arbitrariness, but as an element central to the maintenance of a given narrative. This process has led to a series of works, including Brazil builds (2022) and Acclimatization Garden (2022).

Brazil builds (2022).

Acclimatization Garden (2022).

Concretos

Excedente Monumental (Monumental surplus) in the Concretos exhibition at TEA - Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canarias. Spain.Curated by Gilberto González and Pablo León de la Barra.

2022

Excedente Monumental (Monumental surplus). 2020. Expanded polystyrene, fiberglass and cement. Variable dimensions.

Excedente Monumental (Monumental surplus). 2020. Expanded polystyrene, fiberglass and cement. Variable dimensions.

Photos: Teresa Arozena

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes exhibe 'Concretos', una exposición curada por Gilberto González y Pablo León de la Barra.

Con la participación de Talles Lopes, Rafa Munarriz, Pablo Accinelli, Andreas Valentín, Josep Vilageliu, Federico Assler, Nancy Holt, Guy Tillim, June Crespo, Jane & Louise Wilson, Alexander Apóstol, Marcelo Cidade, Pérez y Requena, Esther Gatón, Adrien Missika, Clara Ianni, Céline Condorelli, Federico Herrero, Andreas Angelidakis, Abraham Riverón y Cyprien Gaillard.

Esta muestra estará abierta hasta el 8 de enero de 2023. Entrada libre.

Esta exposición es una coproducción entre TEA y MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León.

Dentro del programa de TEA, la arquitectura como materialización de una imagen tiene un papel central. Al recurrir al cemento como elemento sobre el que sustentar relaciones entre obras, somos conscientes de la aparente insustancialidad discursiva. Sin embargo, al circunscribirla a un periodo concreto de la tardomodernidad se establecen una serie de conexiones vinculadas a los flujos de capital y los procesos políticos. Como material de una enorme ductilidad permitió una renovación plástica de la arquitectura a la vez que supuso una emancipación de los cánones estilísticos, por otro lado supone el acceso de capas de la población, especialmente en el ámbito urbano, a procesos de autoconstrucción con programas propios en relación a la capacidad transformadora del material.

La irrupción del brutalismo y todas sus neo variantes sin embargo vienen a coincidir en Latinoamérica con el inicio del fin de los procesos democráticos que son antesala de los programas neoliberales. Paradójicamente en España vienen a suponer la plasmación procesos de apertura que sin embargo afianzan el programa de igual forma neoliberal. La exposición plantea una constelación de artistas que a través del concreto -cemento- analizan los procesos de quiebra social y reforzamiento del capital hasta desembocar en procesos neofeudalistas.

Con la participación de Talles Lopes, Rafa Munarriz, Pablo Accinelli, Andreas Valentín, Josep Vilageliu, Federico Assler, Nancy Holt, Guy Tillim, June Crespo, Jane & Louise Wilson, Alexander Apóstol, Marcelo Cidade, Pérez y Requena, Esther Gatón, Adrien Missika, Clara Ianni, Céline Condorelli, Federico Herrero, Andreas Angelidakis, Abraham Riverón y Cyprien Gaillard.

Esta muestra estará abierta hasta el 8 de enero de 2023. Entrada libre.

Esta exposición es una coproducción entre TEA y MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León.

Dentro del programa de TEA, la arquitectura como materialización de una imagen tiene un papel central. Al recurrir al cemento como elemento sobre el que sustentar relaciones entre obras, somos conscientes de la aparente insustancialidad discursiva. Sin embargo, al circunscribirla a un periodo concreto de la tardomodernidad se establecen una serie de conexiones vinculadas a los flujos de capital y los procesos políticos. Como material de una enorme ductilidad permitió una renovación plástica de la arquitectura a la vez que supuso una emancipación de los cánones estilísticos, por otro lado supone el acceso de capas de la población, especialmente en el ámbito urbano, a procesos de autoconstrucción con programas propios en relación a la capacidad transformadora del material.

La irrupción del brutalismo y todas sus neo variantes sin embargo vienen a coincidir en Latinoamérica con el inicio del fin de los procesos democráticos que son antesala de los programas neoliberales. Paradójicamente en España vienen a suponer la plasmación procesos de apertura que sin embargo afianzan el programa de igual forma neoliberal. La exposición plantea una constelación de artistas que a través del concreto -cemento- analizan los procesos de quiebra social y reforzamiento del capital hasta desembocar en procesos neofeudalistas.

The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul

Project for the National Art Salon of Goiás. MAC GO - Museum of Contemporary Art of Goiás. Brasil.2022.

The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul. Acrylic on canvas. 600 x 200 x 300 cm. 2022. (Photo: Paulo Rezende).

The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul. Acrylic on canvas. 600 x 200 x 300 cm. 2022.

There were only 8 courses of architecture in Brazil until the 1960s, according to the diagnosis of the architect and researcher Hugo Segawa, with the exception of Brasilia and Minas Gerais, the other centers were distributed among coastal states such as São Paulo, Pernambuco, Ceará and Rio Grande do Sul. The other regions, especially those far from the coast, began to have a more effective circulation of architects only after the 1970s, with the state plans for national integration and the creation of schools of architecture outside the traditional metropolitan centers.

Preceding this period, the years of mobilization around the construction of Brasília promoted years of expressive expansion of urban areas in the interior of Brazil, built mostly by non-architects such as bricklayers, engineers, draftsmen and often by the inhabitants or owners of these buildings themselves. This diagnosis of a supposed absence of architects, together with the massive diffusion of signs of modernity in this period, may have resulted in the vast amount of popular buildings scattered throughout Brazil that appropriated the modernist architectural stylistics present in Brasília, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the first completed building of the capital.

In parallel to the rare presence of architecture schools in the interior of the country in the 20th century, there is the low occurrence of art schools based on the Western canons of Fine Arts. It is more common to see workers alternating in practices that ranged from the making of signs, posters, and billboards for movie theaters to the making of copies of classical paintings to serve middle-class families settled in the country's interior. In general, these practices were based on the idea of copying and/or reproducing pre-existing images, but directly based on particular and local ways of execution.

In this sense, one can speculate that the advance of a series of narratives of modernity, detached from institutions and structures that are often related to the idea of modernization, may have characterized a common practice among a broad and heterogeneous group of workers in the interior of Brazil: through the logic of copying they appropriated, reinvented, and possibly subverted the signs of modernity produced in the metropolis and disseminated through fields such as architecture and painting.

Noting the perpetuation of these ways of doing until today, the project “The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul“ (2022), as well as the works The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline" (2020) and "Bela Vista Club” (2021), propose collaboration with painters who maintain a practice based on the principle of copy, commissioning these artists to represent sumptuous buildings designed by non-architects who subjectively appropriated the modernist architectural canons in Brazil.

Preceding this period, the years of mobilization around the construction of Brasília promoted years of expressive expansion of urban areas in the interior of Brazil, built mostly by non-architects such as bricklayers, engineers, draftsmen and often by the inhabitants or owners of these buildings themselves. This diagnosis of a supposed absence of architects, together with the massive diffusion of signs of modernity in this period, may have resulted in the vast amount of popular buildings scattered throughout Brazil that appropriated the modernist architectural stylistics present in Brasília, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the first completed building of the capital.

In parallel to the rare presence of architecture schools in the interior of the country in the 20th century, there is the low occurrence of art schools based on the Western canons of Fine Arts. It is more common to see workers alternating in practices that ranged from the making of signs, posters, and billboards for movie theaters to the making of copies of classical paintings to serve middle-class families settled in the country's interior. In general, these practices were based on the idea of copying and/or reproducing pre-existing images, but directly based on particular and local ways of execution.

In this sense, one can speculate that the advance of a series of narratives of modernity, detached from institutions and structures that are often related to the idea of modernization, may have characterized a common practice among a broad and heterogeneous group of workers in the interior of Brazil: through the logic of copying they appropriated, reinvented, and possibly subverted the signs of modernity produced in the metropolis and disseminated through fields such as architecture and painting.

Noting the perpetuation of these ways of doing until today, the project “The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul“ (2022), as well as the works The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline" (2020) and "Bela Vista Club” (2021), propose collaboration with painters who maintain a practice based on the principle of copy, commissioning these artists to represent sumptuous buildings designed by non-architects who subjectively appropriated the modernist architectural canons in Brazil.

Bela Vista Club

2021 Bela Vista Club. Acrylic on canvas. 272 x 488 cm. 2021.

Bela Vista Club. Acrylic on canvas. 272 x 488 cm. 2021. (Photo: Paulo Rezende).

There were only 8 courses of architecture in Brazil until the 1960s, according to the diagnosis of the architect and researcher Hugo Segawa, with the exception of Brasilia and Minas Gerais, the other centers were distributed among coastal states such as São Paulo, Pernambuco, Ceará and Rio Grande do Sul. The other regions, especially those far from the coast, began to have a more effective circulation of architects only after the 1970s, with the state plans for national integration and the creation of schools of architecture outside the traditional metropolitan centers.

Preceding this period, the years of mobilization around the construction of Brasília promoted years of expressive expansion of urban areas in the interior of Brazil, built mostly by non-architects such as bricklayers, engineers, draftsmen and often by the inhabitants or owners of these buildings themselves. This diagnosis of a supposed absence of architects, together with the massive diffusion of signs of modernity in this period, may have resulted in the vast amount of popular buildings scattered throughout Brazil that appropriated the modernist architectural stylistics present in Brasília, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the first completed building of the capital.

In parallel to the rare presence of architecture schools in the interior of the country in the 20th century, there is the low occurrence of art schools based on the Western canons of Fine Arts. It is more common to see workers alternating in practices that ranged from the making of signs, posters, and billboards for movie theaters to the making of copies of classical paintings to serve middle-class families settled in the country's interior. In general, these practices were based on the idea of copying and/or reproducing pre-existing images, but directly based on particular and local ways of execution.

In this sense, one can speculate that the advance of a series of narratives of modernity, detached from institutions and structures that are often related to the idea of modernization, may have characterized a common practice among a broad and heterogeneous group of workers in the interior of Brazil: through the logic of copying they appropriated, reinvented, and possibly subverted the signs of modernity produced in the metropolis and disseminated through fields such as architecture and painting.

Noting the perpetuation of these ways of doing until today, the project "Bela Vista Club” (2021), as well as the works The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline" (2020) and "The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul" (2022), propose collaboration with painters who maintain a practice based on the principle of copy, commissioning these artists to represent sumptuous buildings designed by non-architects who subjectively appropriated the modernist architectural canons in Brazil.

The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline

2020.The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline. Acrylic on canvas, 280 x 400 cm. Photo: Ricardo Miyada / Tomie Ohtake Institute.

7th EDP Foundation Award. 2020. Instituto Tomie Ohtake. Sao Paulo, Brazil. Photo: Ricardo Miyada / Tomie Ohtake Institute.

The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline. Acrylic on canvas, 280 x 400 cm. Photo: Ricardo Miyada / Tomie Ohtake Institute.

Bench in the Santo Antônio church square (Três Lagoas - MS). 2020. Tamboril wood furniture (110 x 35 x 42 cm). Photo: Paulo Rezende.

The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline. Acrylic on canvas, 280 x 400 cm. Photo: Paulo Rezende.

There were only 8 courses of architecture in Brazil until the 1960s, according to the diagnosis of the architect and researcher Hugo Segawa, with the exception of Brasilia and Minas Gerais, the other centers were distributed among coastal states such as São Paulo, Pernambuco, Ceará and Rio Grande do Sul. The other regions, especially those far from the coast, began to have a more effective circulation of architects only after the 1970s, with the state plans for national integration and the creation of schools of architecture outside the traditional metropolitan centers.

Preceding this period, the years of mobilization around the construction of Brasília promoted years of expressive expansion of urban areas in the interior of Brazil, built mostly by non-architects such as bricklayers, engineers, draftsmen and often by the inhabitants or owners of these buildings themselves. This diagnosis of a supposed absence of architects, together with the massive diffusion of signs of modernity in this period, may have resulted in the vast amount of popular buildings scattered throughout Brazil that appropriated the modernist architectural stylistics present in Brasília, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the first completed building of the capital.

In parallel to the rare presence of architecture schools in the interior of the country in the 20th century, there is the low occurrence of art schools based on the Western canons of Fine Arts. It is more common to see workers alternating in practices that ranged from the making of signs, posters, and billboards for movie theaters to the making of copies of classical paintings to serve middle-class families settled in the country's interior. In general, these practices were based on the idea of copying and/or reproducing pre-existing images, but directly based on particular and local ways of execution.

In this sense, one can speculate that the advance of a series of narratives of modernity, detached from institutions and structures that are often related to the idea of modernization, may have characterized a common practice among a broad and heterogeneous group of workers in the interior of Brazil: through the logic of copying they appropriated, reinvented, and possibly subverted the signs of modernity produced in the metropolis and disseminated through fields such as architecture and painting.

Noting the perpetuation of these ways of doing until today, the project “The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline“ (2022), as well as the works “The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul" (2020) and"Bela Vista Club” (2021), propose collaboration with painters who maintain a practice based on the principle of copy, commissioning these artists to represent sumptuous buildings designed by non-architects who subjectively appropriated the modernist architectural canons in Brazil.

Preceding this period, the years of mobilization around the construction of Brasília promoted years of expressive expansion of urban areas in the interior of Brazil, built mostly by non-architects such as bricklayers, engineers, draftsmen and often by the inhabitants or owners of these buildings themselves. This diagnosis of a supposed absence of architects, together with the massive diffusion of signs of modernity in this period, may have resulted in the vast amount of popular buildings scattered throughout Brazil that appropriated the modernist architectural stylistics present in Brasília, especially the column of the Alvorada Palace (1958), the first completed building of the capital.

In parallel to the rare presence of architecture schools in the interior of the country in the 20th century, there is the low occurrence of art schools based on the Western canons of Fine Arts. It is more common to see workers alternating in practices that ranged from the making of signs, posters, and billboards for movie theaters to the making of copies of classical paintings to serve middle-class families settled in the country's interior. In general, these practices were based on the idea of copying and/or reproducing pre-existing images, but directly based on particular and local ways of execution.

In this sense, one can speculate that the advance of a series of narratives of modernity, detached from institutions and structures that are often related to the idea of modernization, may have characterized a common practice among a broad and heterogeneous group of workers in the interior of Brazil: through the logic of copying they appropriated, reinvented, and possibly subverted the signs of modernity produced in the metropolis and disseminated through fields such as architecture and painting.

Noting the perpetuation of these ways of doing until today, the project “The Great Novo Aripuanã Shoreline“ (2022), as well as the works “The old Forum of Cruzeiro do Sul" (2020) and"Bela Vista Club” (2021), propose collaboration with painters who maintain a practice based on the principle of copy, commissioning these artists to represent sumptuous buildings designed by non-architects who subjectively appropriated the modernist architectural canons in Brazil.

Acclimatization Garden

2022Photos: Thales Leite

Acclimatization Garden

Silkscreen and low-relief engraving on concrete. 40 x 65 x 3 cm.

2022

During my residency at Delfina Foundation (2022) in London, I dedicated myself to investigating a specific question that has been permeating my work for some time now: how did the Brazilian modernist program update and perpetuate narratives that befit the colonial heritages in Brazil, from buildings to its public debating platforms (such as publications and exhibitions)?

With this question in mind, I opted to search for catalogs and exhibition files that proposed to present the modernist production from Brazilian architecture to the global North mid-20th century. Throughout this process, I had my attention drawn to the way vegetation was articulated in the exhibition space in some of these exhibitions. In EXPO 58’s Brazilian pavilion (Brussels, 1958) [1], tropical plants “compete” with architectural photography, whereas in “Brazil Builds” (New York, 1943) they are presented on displays just like the architectural models, leaving from a purely ornamental domain to an exhibition domain.